Photographs of dead people, oh my.

(This is an update of an old piece written for the now-deceased site Horrified, which opened a column for contributors to share the moments that meant the most to them, the flesh and blood of their horror experience. What chilled blood and warmed hearts. A jolt of electricity or two and, like a shambling patchwork corpse, it’s resurrected for this blog.)

Horror. It bewitches us, fires our imagination, burns itself into our being. There’s a lot to the genre we love and what connects us with it the most. It’s in the stories, the emotions, the atmosphere, the aesthetics. And it’s in the moments we find and the impact they have, from jarring scare to creeping, lingering dread. Most often it is these moments that stay with us and inform how we feel about a film, or television show or book.

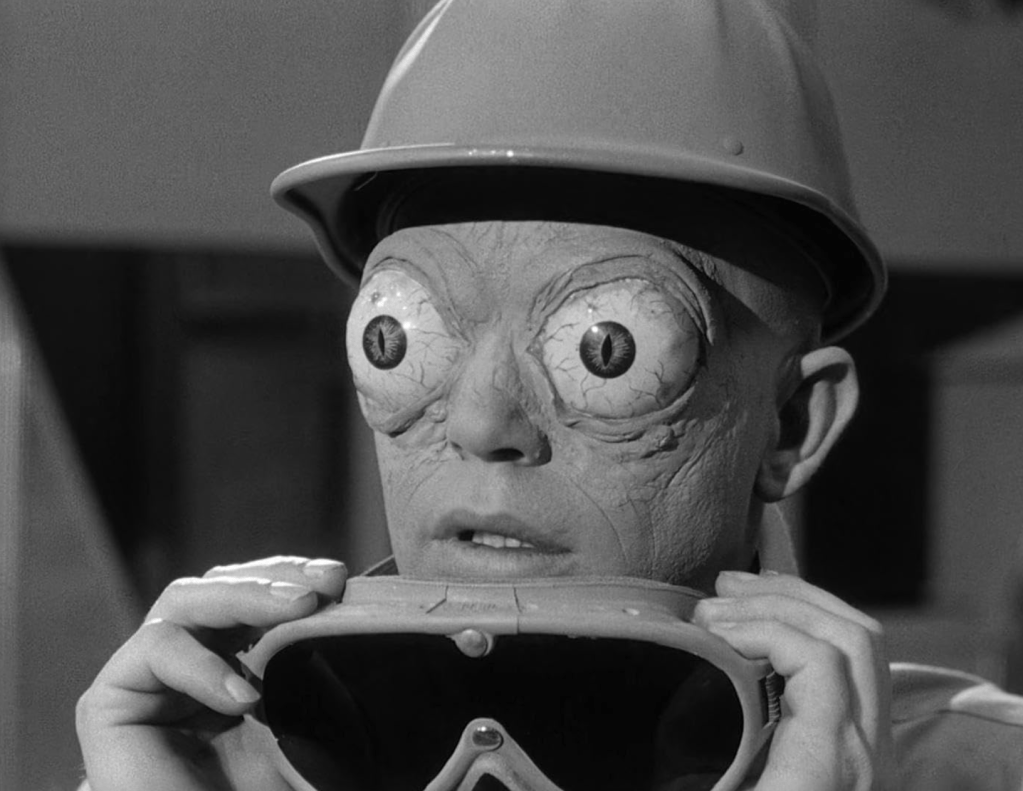

It’s in that zoom to Christopher Lee’s pitiful creature unravelling its bandages and moving from confusion to murderous rage in The Curse of Frankenstein (1957, dir. Terence Fisher). Or in Peter Vaughan’s desperate and doomed attempt to escape the the curse he has brought on himself in A Warning to the Curious (1972, dir. Lawrence Gordon Clark). Or those final, chilling moments of Ghostwatch (1992, dir. Lesley Manning) when we realise there will be no happy ending. It is moments like these that resonate with us and evoke the most visceral responses.

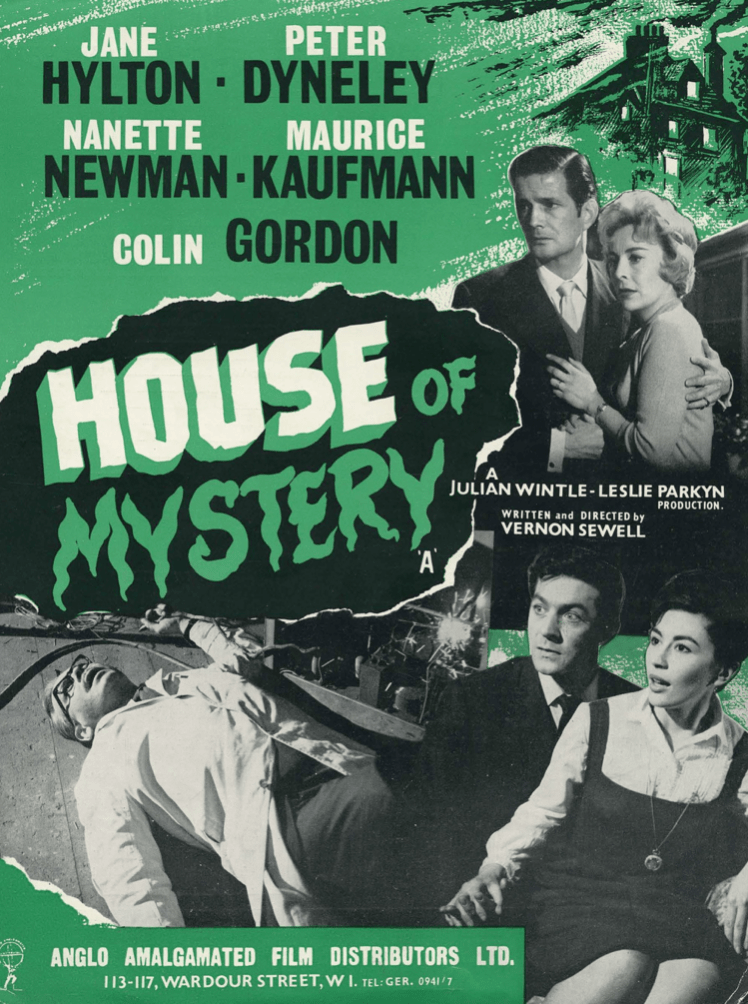

My experience will be familiar to anyone who grew up in the seventies, eighties and into the nineties. Back in these pre-internet days, a burgeoning horror fan still had much to choose from. From television showings of classic films in the wee hours to horror running through Baker-era Doctor Who’s DNA to huge hits like The X-Files, and a multitude of books, magazines and comics, these decades were awash with plenty to thrill the spookily-inclined. It was the halcyon days of monster magazines, fanzines, and short-lived but still fondly remembered comic titles like Scream! (1984). As the Scarred for Life team have demonstrated in their multi-volume hymn to what terrified people in the seventies and eighties, horror rippled through these years and continued to captivate more converts as the new millennium approached.

Despite this, back in those days, we could not look up the history of a film or series or book with a few clicks or taps of a screen. It was the days of mail order, local discovery in your comic shop or newsagent of choice, or shared between friends like niche contraband. And it was not cosy or kind. It was gory film images in copies of Fangoria or latterly The Dark Side. It was sleepy, half-glimpsed nightmares in late night showings. On occasion, these images, these photographs were of something real, too. Magazines would do stories on ghosts ‘caught on film’. Issues of The Unexplained: Mysteries of Mind, Space and Time (Orbis Publishing, 1980-1983) were filled with mind-altering, frequently terrifying stories which were so wild they could only be true. And, in one of his television series devoted to exploring phenomena, Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers (Yorkshire Television, 1985), the author focussed on ‘Fairies, Phantoms and Fantastic Photographs’ (Ep 7, 22 May 1985).

There is one photo discovery from this era that lingers with me the most. The Spectre of Newby Church was bad enough, but the picture taken of Mrs Ellen Hammell by her daughter was the stuff of beguiling nightmare. In 1959, Mabel Chinnery had taken a photo of her husband sat in their car, but when developed there was a passenger of sorts. Behind her husband sat Ellen, Mabel’s recently departed mother. She had been dead a week. It’s grainy and Mrs Hammell’s straight posture is unnerving enough. But where the eyes should be is only white, like some sort of terrifying gateway into the beyond. When you are young, you don’t know anything about double exposures, trick photography or anything else that would explain it away. And this isn’t a film or show, it’s real. On film. Right there; a ghost. As an adult my rational mind knows there is an explanation for it, that there is (on the balance of available evidence) no ghost ever caught on film. And yet…

It would probably be remarkable for Mabel Chinnery to learn that, for me and for others, this image and ones like it opened a door onto other worlds and possibilities in a way films, television and books could not. It frightened me to my very core, and yet I could not look away, because of the possibility of something horrific being actually tangible. Perhaps inescapable. Just like a love of horror.