We all love a long movie, right? Two hours, three hours, lost in the magic of cinema. Well…maybe not all the time. Fortunately, the art of the short film has been there since the earliest days of the medium. There’s a wealth of funny, moving, weird, creepy, thrilling and adventurous entertainment that won’t numb your arse or sap your will to live. And so, I welcome you to this spooky short (mostly) silent film specific edition of Ghoulishly Good Times.

Barbe-bleue (aka Bluebeard, 1901, dir. George Méliès) retells the French legend of a dubious – but very rich – old dodger courting his eighth wife, the seven before her having died ‘in mysterious circumstances’. His new wife is not impressed with being dumped with the danger, nor is she too happy being left bored in his castle while he buggers off. He does leave her, however, with the key to the place and instructions not to get curious, after which she stumbles on the truth of what befell his other wives. What starts as a broad comedy of over gesticulating takes a hard swerve into serious darkness about halfway through. Surreal nightmares, ghosts, a demonic sprite and some deeply unsettling imagery drive it to the reveal of whether wife number eight is destined for the same fate. What we have here, for me, is some of the first flourishing of narrative horror with a bravura shift in tone from ‘oh this is fun’ to ‘holy shit that’s dark’ that became familiar to movie-going horror audiences across the following decades, done here early and in style.

Alongside the development of photography and film and the tantalising prospect of recorded proof (or the lack of it), the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th continued a pronounced split between people who wanted to believe in an afterlife and that people we had lost could be reached there, and those that saw it as a grift designed to exploit vulnerability and grief. This can be seen in the differing beliefs of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini (two men who were nevertheless friends) as fraud and debunking entered into a new phase, and the urgency to believe was shaped by the scale of previously unimaginable loss of life world conflicts inflicted. The UK short Is Spiritualism a Fraud? – The Medium Exposed (1906, dir. J.H. Martin) isn’t really asking a question, but instead presents a couple of con artists getting caught in the act of faking communication with the dead, after which those duped take their revenge in an escalating sequence of slapstick violence. It’s not subtle stuff, but it is a fascinating and entertaining example of the innovation happening in Britain at the time, giving us some startling horror-informed imagery along the way. Enjoyably vicious too, reflecting the way some people felt about the cruelty of offering a bogus way of contact with people lost to them.

Le Spectre Rouge (aka The Red Spectre, 1907, dirs. Segundo de Chomón, Ferdinand Zecca) is a trick film, ostensibly comparable to the Méliès style. Though it’s easy to say everything followed his work, like D.W. Griffith inventing and perfecting every cinema technique you’ve ever heard of, it’s neither true nor fair. This one is its own thing, and has a demonic magician hanging out in his underground lair, dicking about with tricks that seem largely designed to torment women. His attempts are interrupted by a good sprite who intervenes, stopping or reversing the mischief he has wrought. That’s pretty much it, the premise being an excuse to have fun with tricks and special effects, something the film does well. It’s a frequently beautiful film that plays as an inventively crafted window into another world, full of splashes of vibrant imagination.

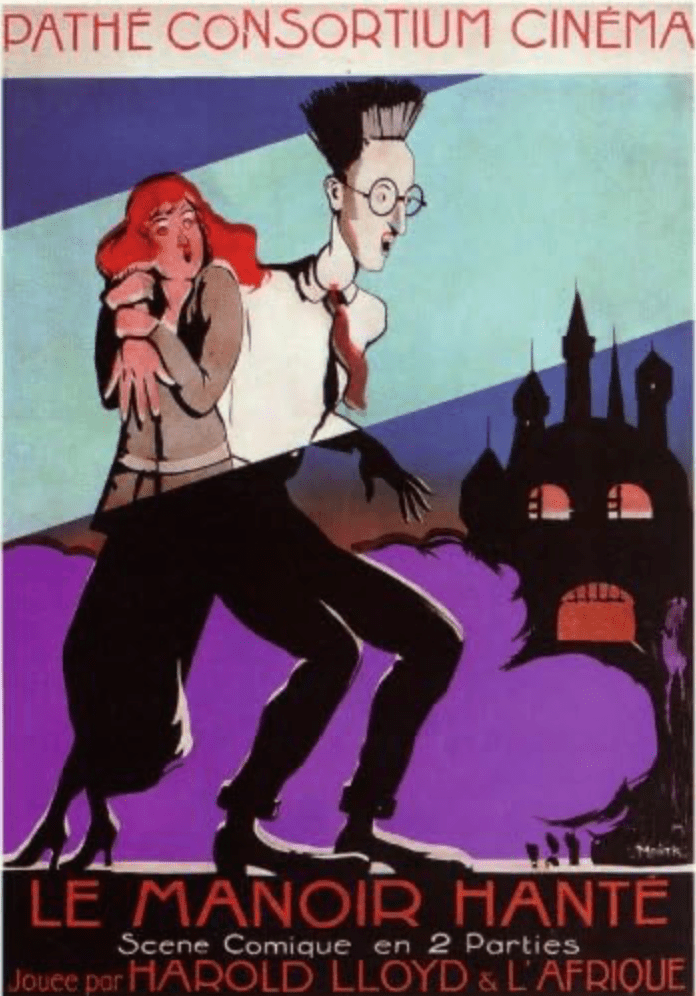

Haunted house movie (and theatre) tropes were already well known by 1920 and ripe for comedic parody. Haunted Spooks (1920, dirs. Hal Roach, Alfred J. Goulding) does just that. But before we get to the titular spooky abode, the film starts with a remarkable sequence where Harold Lloyd’s would-be suitor fails to secure the affections of the woman he loves. This drives him to decide to <ahem> resolve the problem of life permanently through several failed attempts that escalate in a darkly amusing fashion. He’s distracted from any further tries when he runs into a lawyer working on behalf of a young woman who urgently needs a husband to claim her inheritance from her grandfather. Part of that inheritance is a beautiful house that the woman’s uncle covets, and so he does what any reasonable person would: fakes a haunting in the hope it will scare her off. When the couple arrive, we get another sequence of escalating events as the uncle’s ill-considered scheme unravels. There’s a lot to enjoy in this one, not least an intertitle A-game, which doesn’t only complement the action but enhances it (as the best examples did). Lloyd and co-star Mildred Davis make a winning central couple as things get truly hair-raising (makes sense when you see the film). It’s also fair to note that there are some disappointing, tiresome racial ‘gags’ in the second half, so be advised.

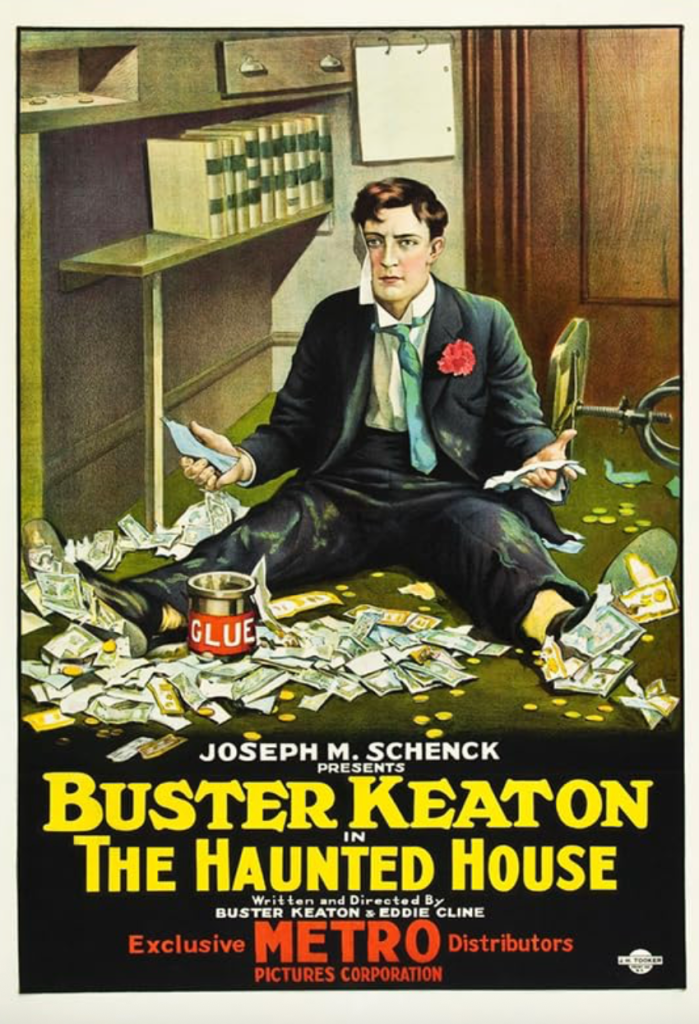

Buster Keaton also got in on the haunted house parody gig in the following year’s…uh…The Haunted House (1921, dirs. Buster Keaton and Edward F. Cline). In this one, bank teller Keaton has a day start badly (gluing cash to his hands) and get worse (on the run from the police, hiding out at a ‘haunted’ mansion). It’s not actually haunted, however, but instead the hideout of a gang of thieves using fake ghosts and ghouls to keep people away from their lair. The entire film is a great example of Keaton’s often bizarre, off-kilter humour. When we get to the hideout, it gets increasingly wrapped up in a building run of visual gags and repeated refrains that land in a final sequence that pays off beautifully. There’s one gorgeous frame after another along the way in this gem. I could write more, but I just recommend seeking it out and enjoying it.

The Fall of the House of Usher (dirs. James Sibley Watson & Melville Webber) was one of two adaptations of Poe’s tale in 1928, both of which traded in surreal visuals (the other a feature-length French version). This one was an American production and gives us an avant-garde take on the story, existing for the purposes of experimenting with imagery, mood and technique. It’s a remarkably close approximation of the recognisable feel of a nightmare. The narrative is still straightforward enough to follow but it’s not the point of the film: that is to use images to make you feel unsettled and unbalanced and it does this very well. I wouldn’t say it’s an enjoyable experience, but it certainly qualifies as horrific and, alongside the range of techniques used here, it’s definitely worth seeking out.

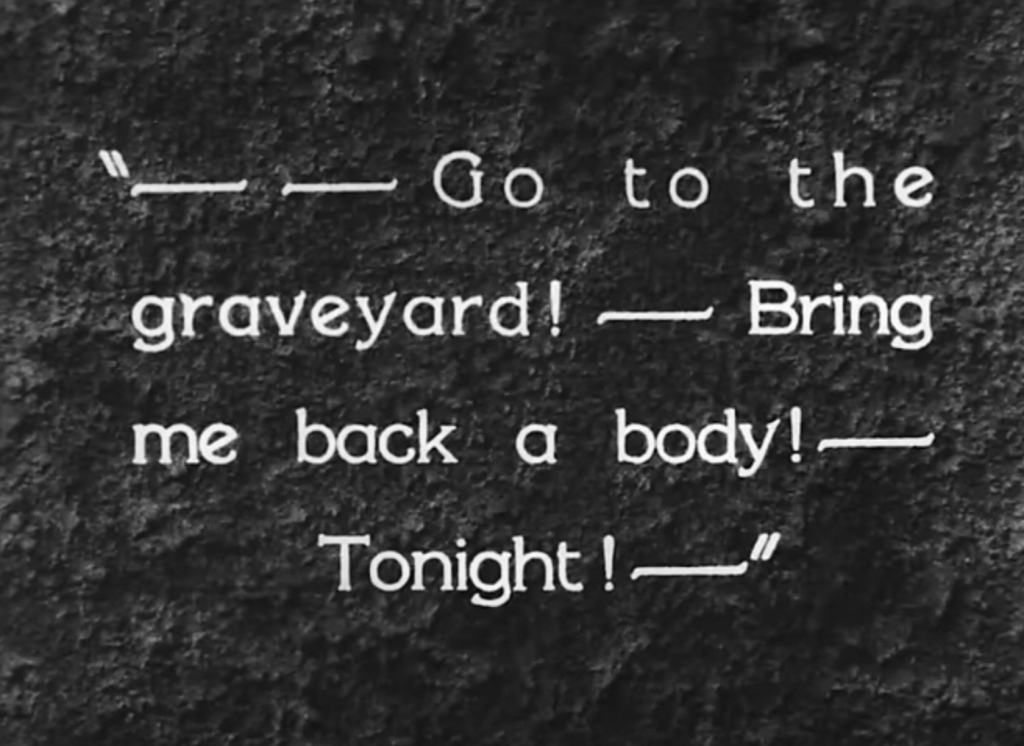

The first Laurel and Hardy film to be released with synchronised sound (here a musical score with sound effects), Habeas Corpus (1928, dirs. Leo McCaret and James Parrott) has the duo knocking on the door of an insane professor (in the hope of work or money, or in Stan’s case, a slice of buttered toast). He offers them $500 to bring him a body back from the cemetery, and despite their misgivings, they accept. They go down to the graveyard, but unbeknown to them, the police are also aware of the potential crime being committed, and head down there too, aiming to pretend to be a ghost and put the duo off. What follows is a film packed with arguably predictable gags and slapstick somehow, as so often the case with these two great performers, made fresh and appealing by the talent and chemistry of Ollie and Stan. There’s also a wilful drawing out of sequences like them trying to scale the wall into the cemetery that makes that something familiar become something fresh – like a different, more cuddly, less confrontationally weird version of the off-kilter Keaton approach. Again, a Laurel and Hardy hallmark. Great fun.

At the end of the decade that started with Lloyd and Keaton encountering fake ghosts, Mickey Mouse ran into the real thing in The Haunted House (1929, dir. Walt Disney). During a storm, Mickey seeks refuge in an abandoned house, only to find himself forced to soundtrack (by playing the organ) a delirious dance-off between the skeletal inhabitants. When he tries to escape, things get weirder still. A horror-comedy building on the same year’s The Skeleton Dance* (1929, dir. Walt Disney), this comes from Disney’s emerging days, when it wasn’t tethered to its later image, and it’s pretty wild, nightmarish stuff. For me, much of this has the feel of a Fulci-esque circular nightmare of the seventies or eighties, where if you found out the mouse was dead and trapped in his own private hell, it would need no further explanation. A ‘happy’ conclusion is inevitable (it is a cartoon after all, you know – for the kids) but if it cut off a few seconds earlier, or ended with Mickey lost in the storm again, discovering the house, that could only make it (slightly) better.

*That one, as the NYT reported in 1931, banned in Denmark for being ‘too macabre’

Though not a horror, a bonus mention for Suspense. (1913, dir. Lois Weber), an excellent home-invasion thriller which finds a woman and her young child in their remote house, abandoned by their maid, and menaced by a passing stranger who finds his way inside. With her husband alerted and racing back from work to try and get there in time, the stranger makes his way through the house, up to her room where she has barricaded herself and her child in. Like several of the above films, the elements are familiar but Weber makes stylish use of technique, frames the story imaginatively, and adds in little shorthand character notes that bring them to life despite the brief running time. An outstandingly good, and perfectly named, film.