It’s that time you’ve all been waiting for, a round-up of Stuff I Have Enjoyed this year, across film, television, books and, very occasionally, music. Some of it might have even been made this century! Although, almost certainly not. This isn’t everything for the year, instead a selection of (mostly) new-to-me highlights.

2025 has been a year where I’ve broadly dropped self-imposed reading targets or anything like that (turns out they’re stressful and feel like a chore when other things preclude you from keeping to them, who knew?). I have replaced this with floating arbitrary goals (do Chaplin’s entire filmography, from the earliest Keystone days! Make lists of all of the films included in books like You Won’t Believe Your Eyes!: A Front Row Look at the Science Fiction and Horror Films of the 1950s!) because they seemed like a good idea at the time, dammit.

That has led me to things like a return to and increased use of Letterboxd, the type of social media I can get behind (limited human interaction? Cool, good stuff) and moving away from pretty much all other platforms (is Bluesky next? Possibly). On Letterboxd I’ve been enjoying logging, reviewing and rating films, despite that being a largely pointless, arbitrary (again!) endeavour.

On that topic, off we go with the round-up.

Silent films

I’ve been really enjoying widening my silent film experience, and this year has included some of my favourites yet.

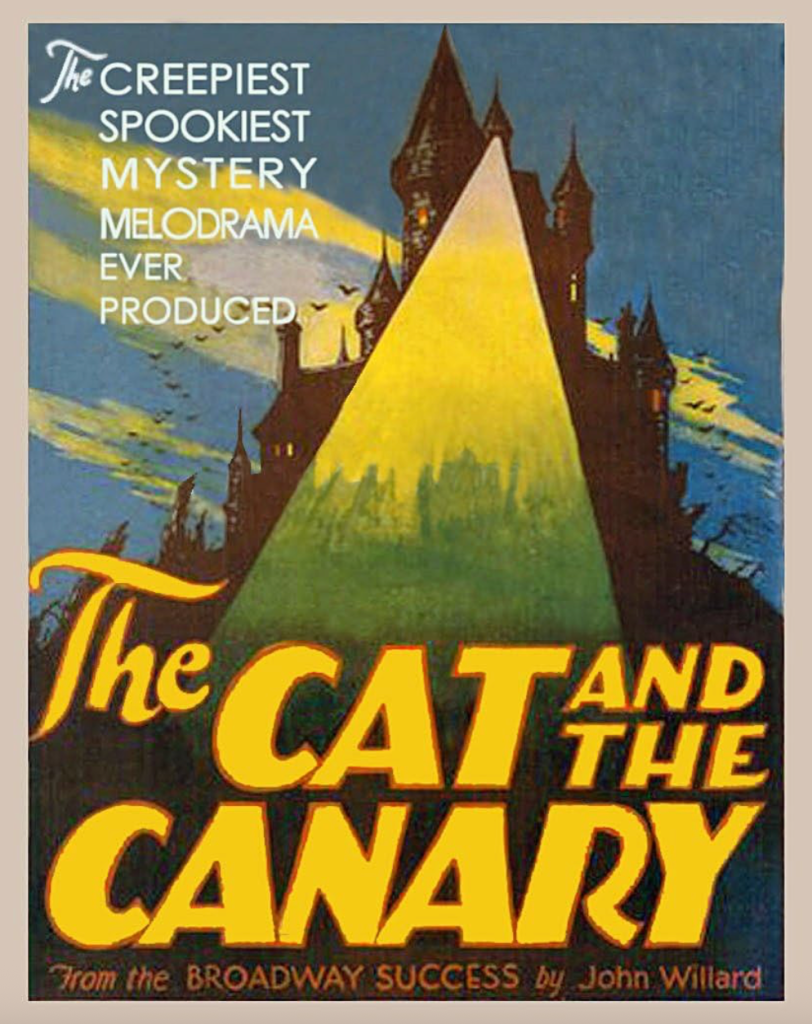

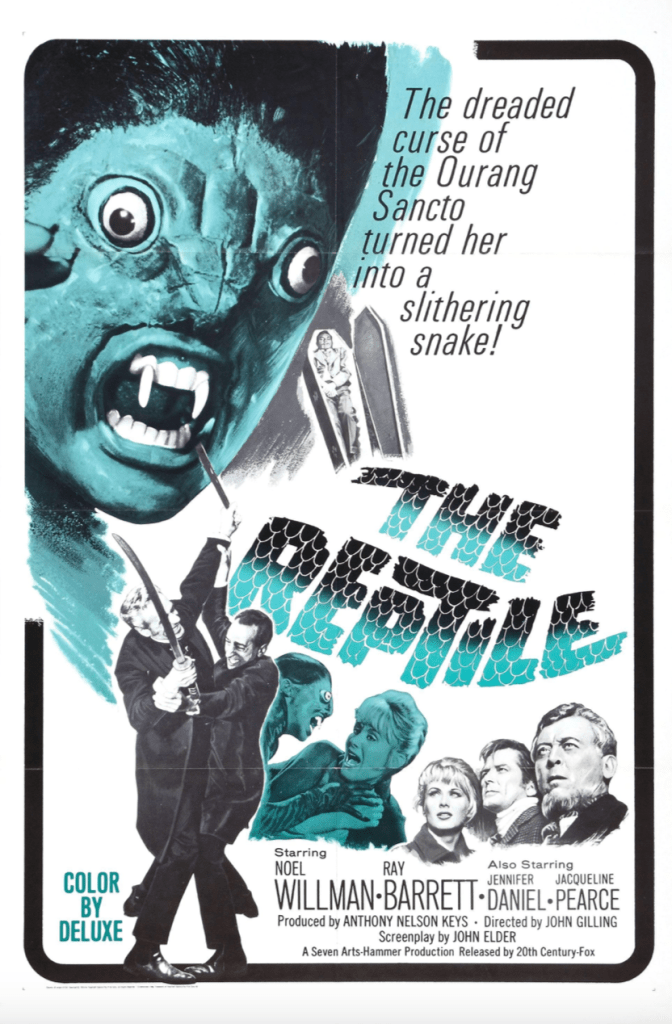

Poster for The Cat and the Canary (1927)

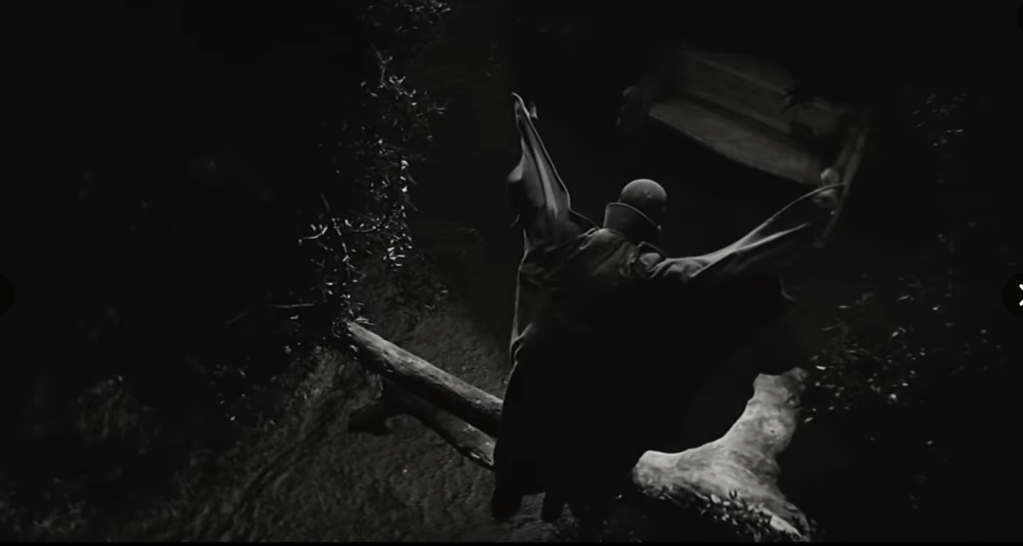

The Cat and the Canary (1927, directed by Paul Leni) takes the familiar-in-1927, overripe tropes of old dark house mysteries and puts a more comedic spin on them, but Leni can’t resist some genuine chills and gorgeously dark imagery, so the film turns out to be one of the best examples of the very thing it is pastiching.

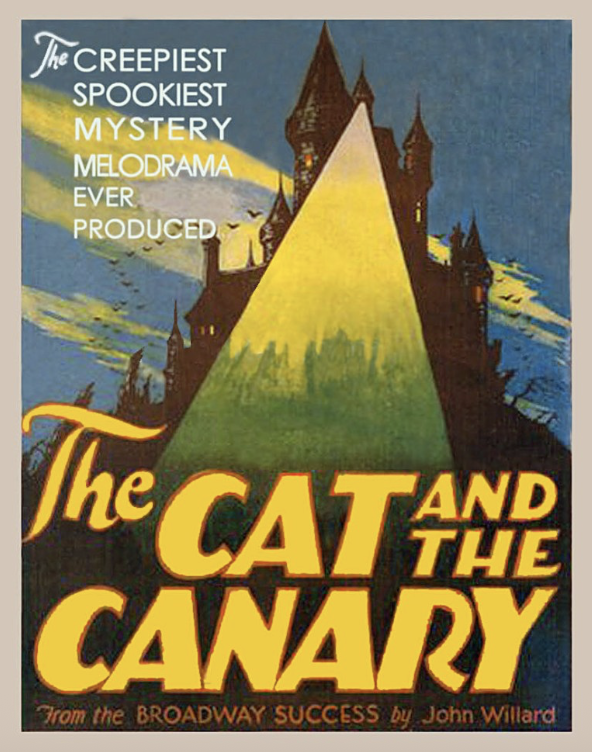

Swedish poster for The Bat (1926)

Roland West’s first go at adapting the stage play The Bat into a feature in 1926 is a similar mix of comedy and serious thrills, evocative imagery, and a good central mystery. Some of the frames in this film should hang in art galleries. Ben Model’s Undercrank Productions label gave this a Blu-ray and DVD release last year that shows it the love it deserves.

Lon Chaney as Erik (the Phantom) at the masquerade ball

For its 100th birthday, Lon Chaney’s The Phantom of the Opera (‘directed’ by Rupert Julian in 1925) was back in cinemas in October and I gained a new appreciation for the film and for one of Lon’s more unsubtle performances. Once his glorious make-up for Erik is revealed, the delirious journey to its brutal conclusion was grand big-screen fun.

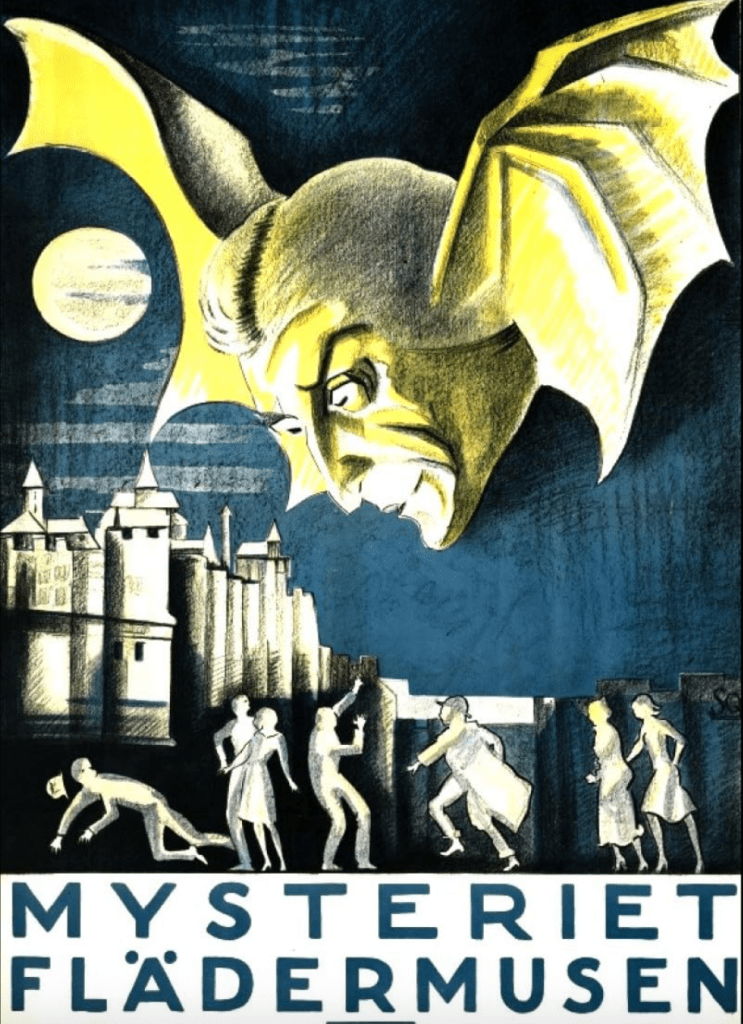

French poster for West of Zanzibar (1928)

On the subject of Chaney, I also hugely enjoyed the utterly reprehensible West of Zanzibar, directed by Tod Browning in 1928, which was wildly inappropriate, grotesque and deeply suspect. It’s also great fun, with a phenomenal Lon holding the entire wild ride together.

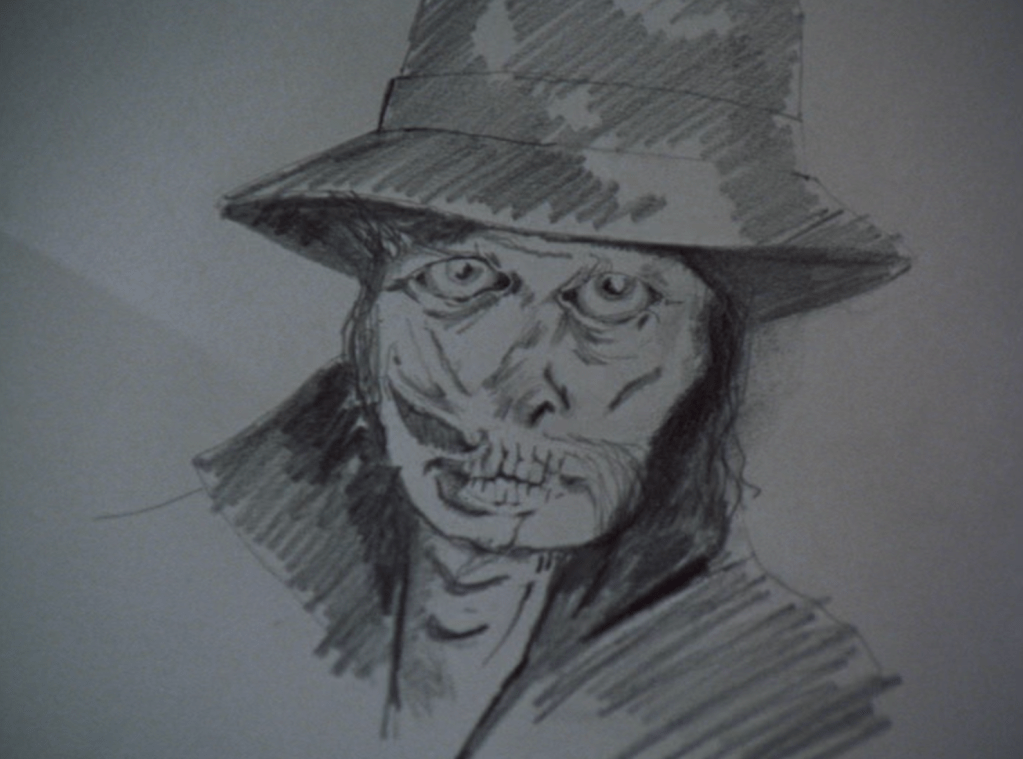

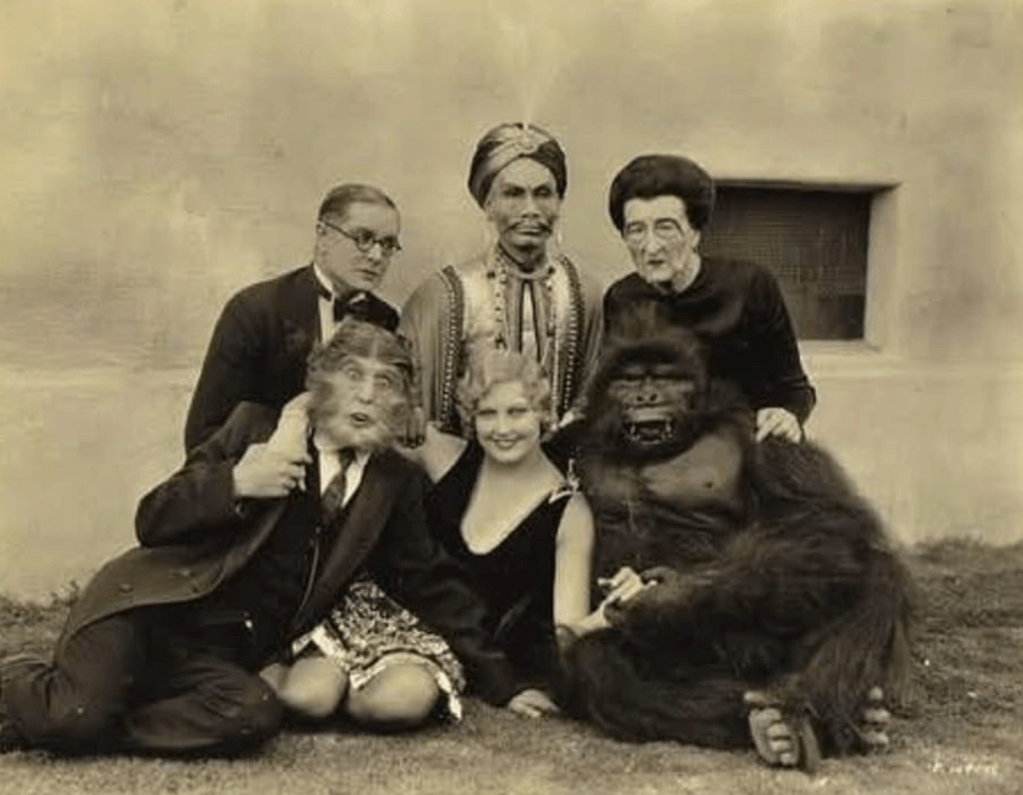

Cast members of Seven Footprints to Satan (1929) in costume

Wilfully frustrating, nightmarish and oddly moving, Seven Footprints to Satan (directed in 1929 by Benjamin Christensen) is best come to knowing as little as possible about it. If the photo above of key cast members doesn’t make you want to watch it now, then I can’t help you.

Short films and cartoons

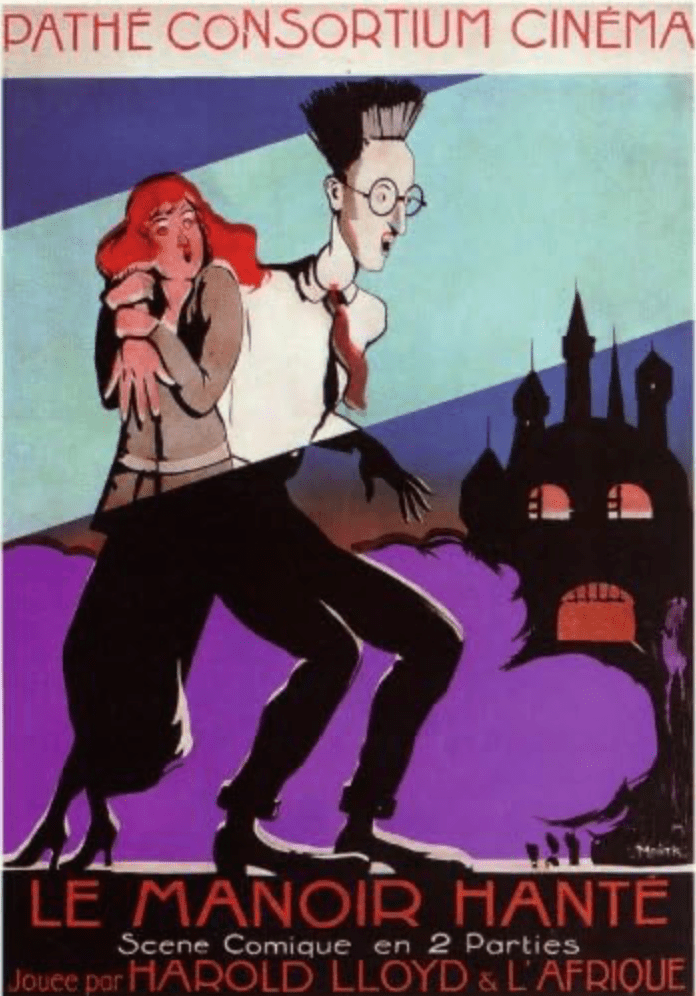

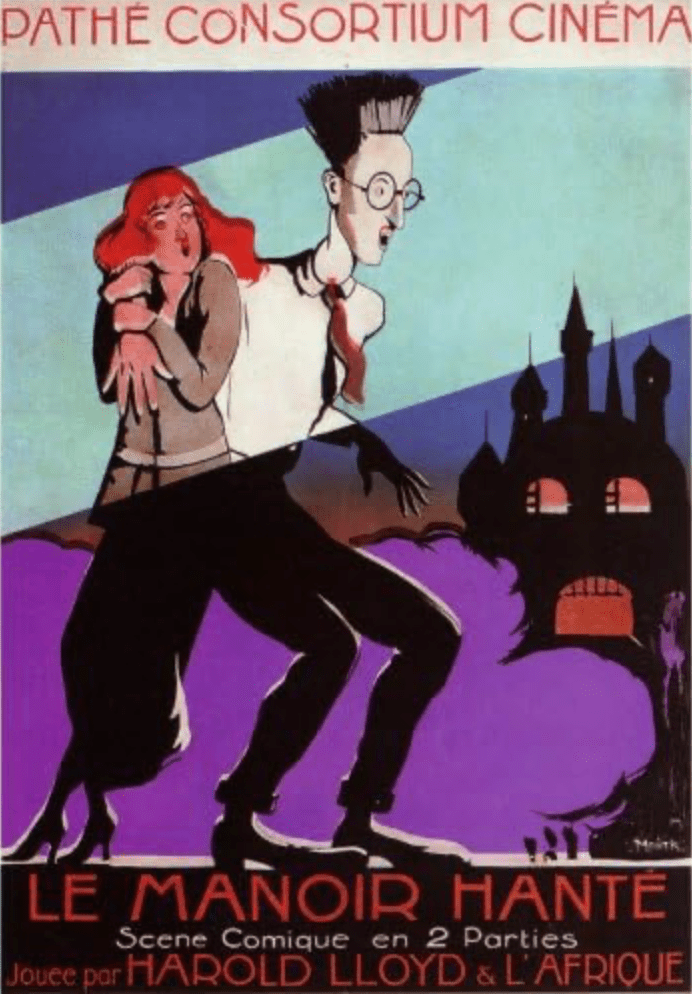

French poster for Haunted Spooks (1920)

The actual haunted house part of Haunted Spooks (directed in 1920 by Hal Roach and Alfred J. Goulding) is decent, silly fun marred by a disappointing raft of racist gags. The first half, which finds Harold Lloyd trying to woo his current love, get rejected, and then decide to end things, only fail every time, is much better. Dark hearted but still delightfully silly, with some excellent gags and delivery.

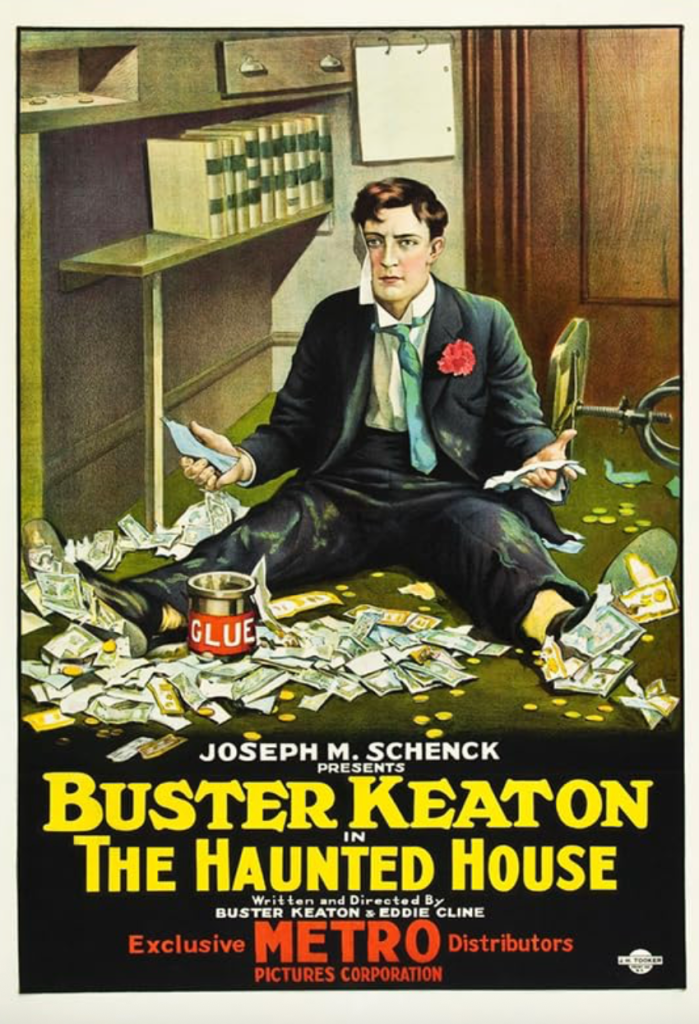

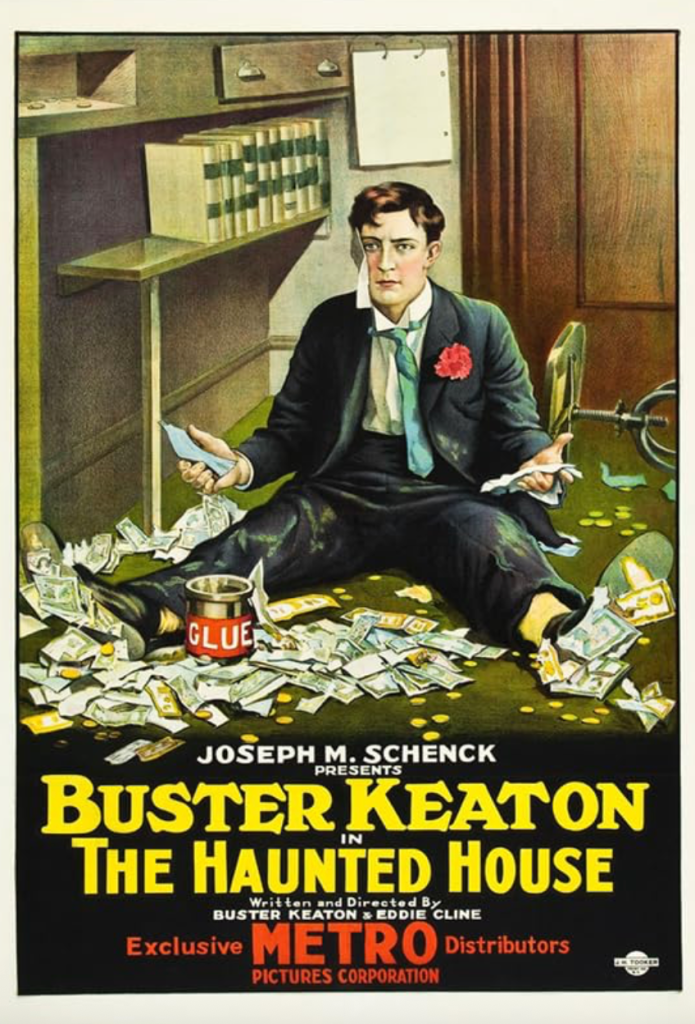

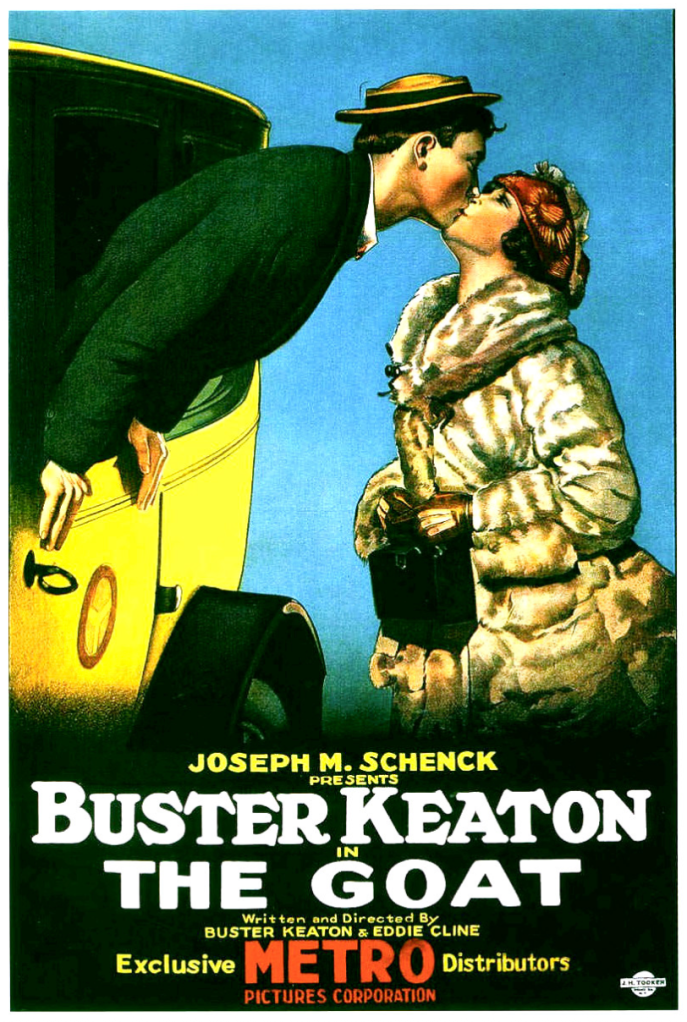

Posters for The Haunted House (1921) and The Goat (1921)

Two favourite Buster Keatons from this year (where every Keaton was good to great) were The Haunted House and The Goat (both directed by Keaton and Eddie Cline, both 1921), the former an inventive run at…uh…haunted house cliches and the latter an at-times jaw-dropping spectacle that has some of the best stunt work and gags he ever did, which means some of the best anyone ever did.

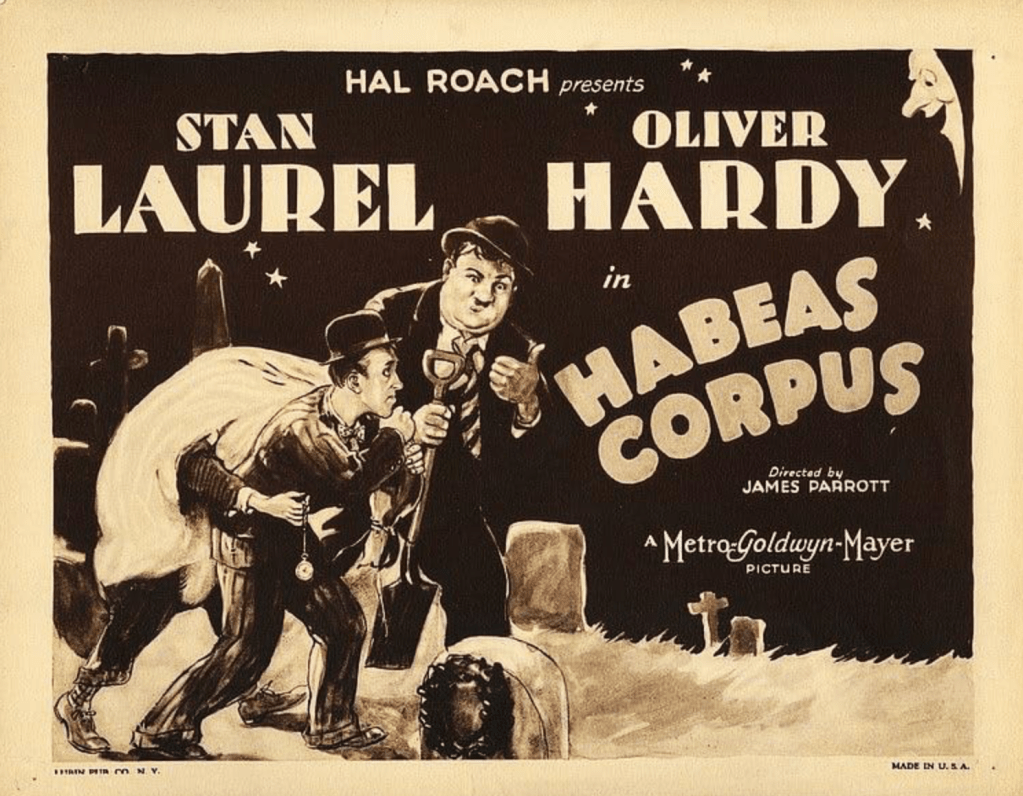

A poster/lobby card for Habeas Corpus (1928)

It might be impossible for me to not enjoy a Laurel and Hardy film from the twenties or thirties, and it hasn’t happened yet, with Habeas Corpus (directed by Leo McCaret and James Parrott in 1928) quickly becoming a new favourite. Their first synchronised sound picture (here meaning a score with sound effects), it’s a classic of The Boys’ broad slapstick, drawn-out gags, silliness, and graveyard shenanigans that I loved.

Mack Swain, Phyllis Allen, and Charlie Chaplin in A Busy Day (1914)

Chaplin’s opening run of Keystone films range from the brilliantly inspired to the dismal, but special mention in this post for A Busy Day (directed by Mack Sennett in 1914), which is almost completely morally irredeemable (extreme violence, barrel-bottom misogyny, utterly formless), but on the day I put it on, Chaplin in drag hoofing the shit out of anyone within kicking distance for 6 minutes before meeting an unfortunate end made me chuckle when I really needed it. Don’t ask me to stand by this assessment in future.

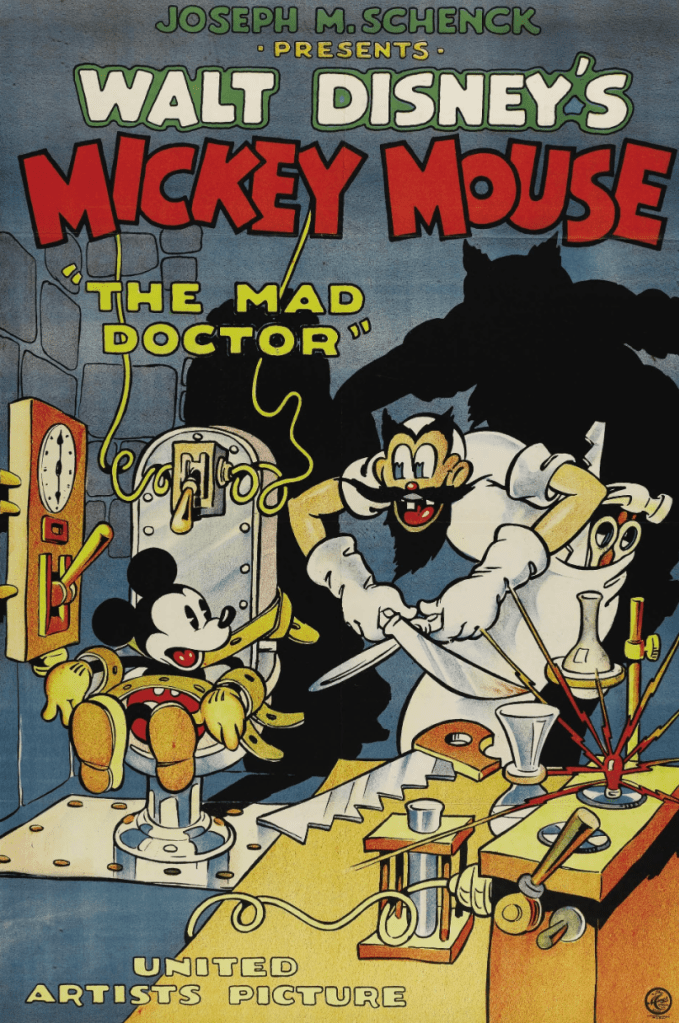

A bad poster for The Haunted House (1929), a good poster for The Mad Doctor (1933)

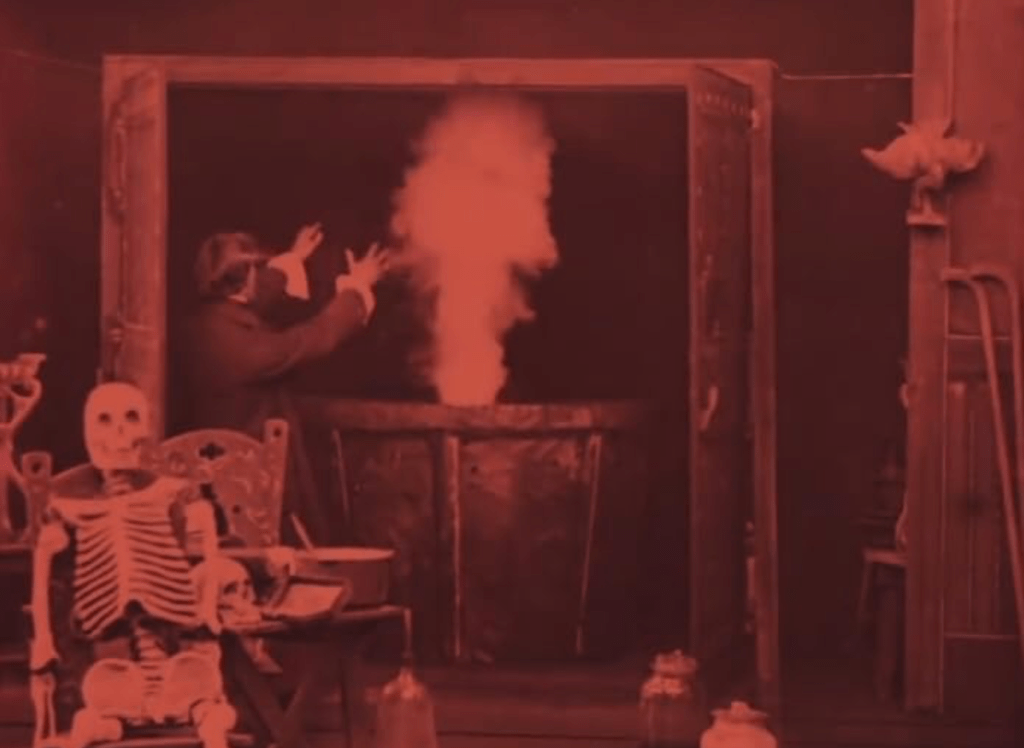

I enjoyed several early cartoon classics this year, but two Mickey Mouse ones stood out, perhaps because of how far they are apart from modern Disney, but definitely because they function as some pretty wild, gnarly horror in their own right. The Haunted House (directed by Walt Disney and Jack King in 1929) and The Mad Doctor (directed by David Hand and Wilfred Jackson in 1933) are stuffed with extraordinary animated imagery and, for the first title in particular, stack up against any serious circular nightmare horror. But you know, for kids.

Sound films

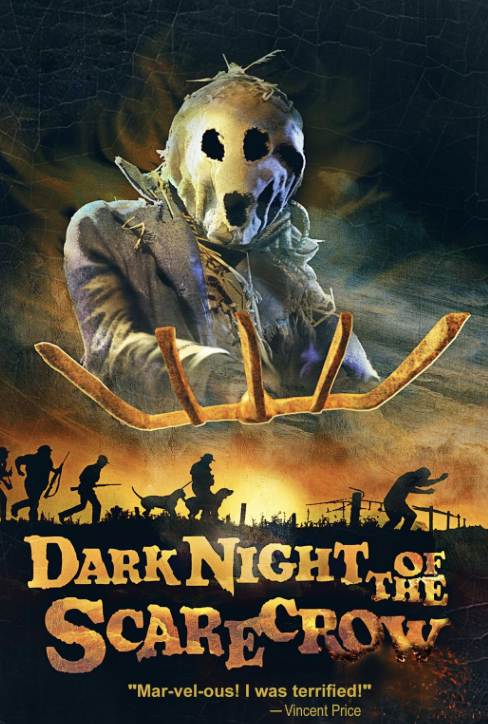

Posters for The Man From Planet X (1951) and Dark Night of the Scarecrow (1981)

A low key science-fiction minor classic and an outstanding television movie horror are first up. Veteran director Edward G. Ulmer’s The Man From Planet X (1951) functions as a kind of proto-Quatermass-y, horror-adjacent yarn in which a spacecraft lands on a foggy Scottish moor, intentions unknown. A journalist and scientist try to find, not that by the film’s conclusion we really know that much more for absolute certain. Game attempts at Scottish accents, solid direction and a properly alien alien are all good fun.

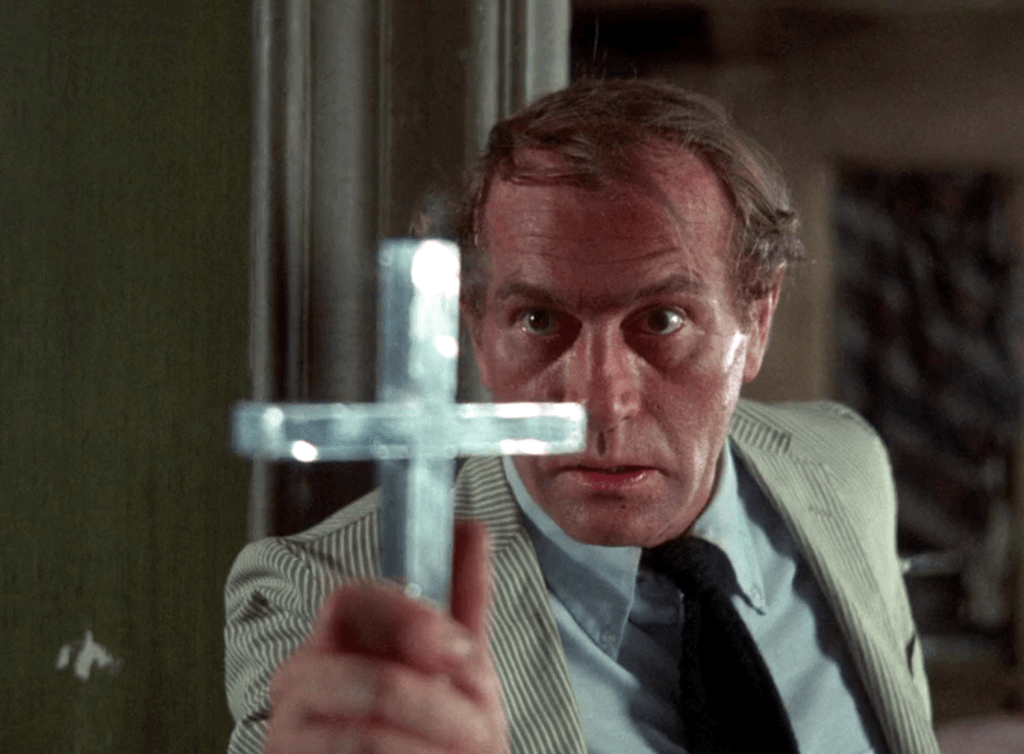

Dark Night of the Scarecrow, directed for television by Frank De Felitta in 1981, is a leisurely paced, beautifully shot, frequently excellent tale of revenge that goes to some very dark places. A great cast is still dominated by a powerhouse, grotesquely villainous turn by Charles Durning as Otis P. Hazelrigg, a deeply unsettling, vile piece of work.

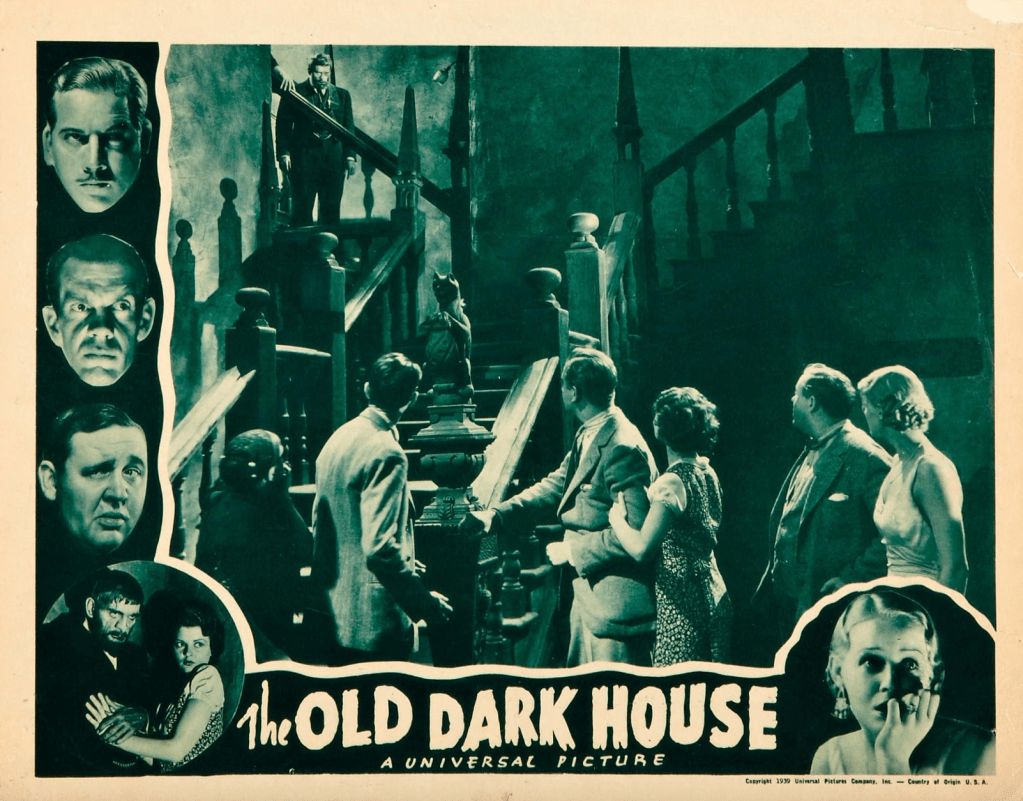

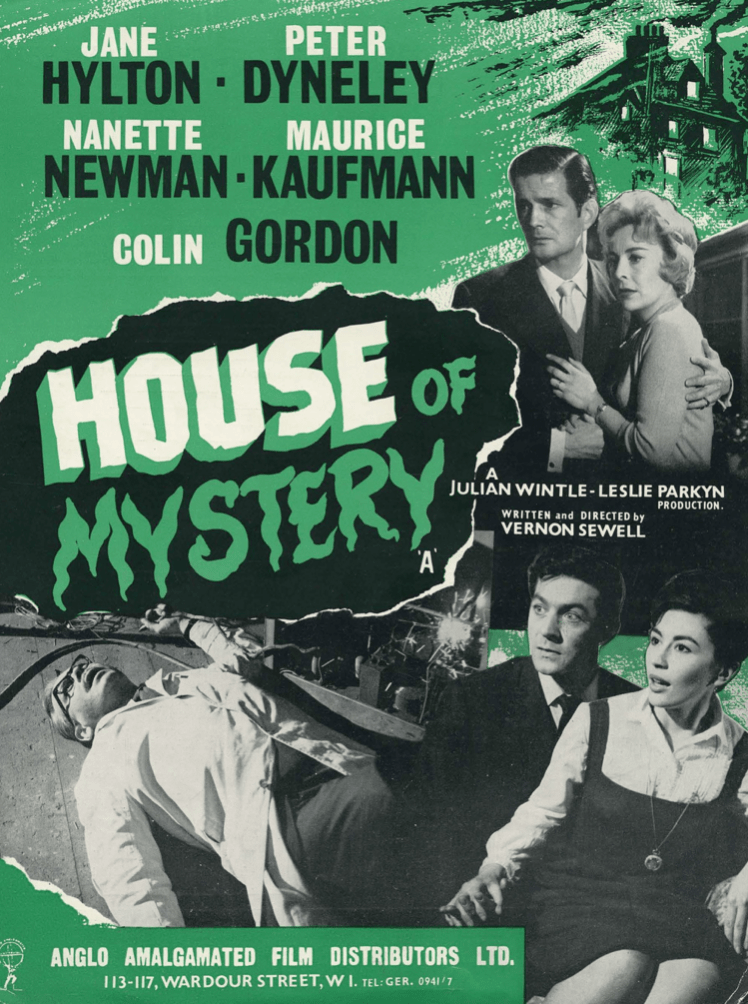

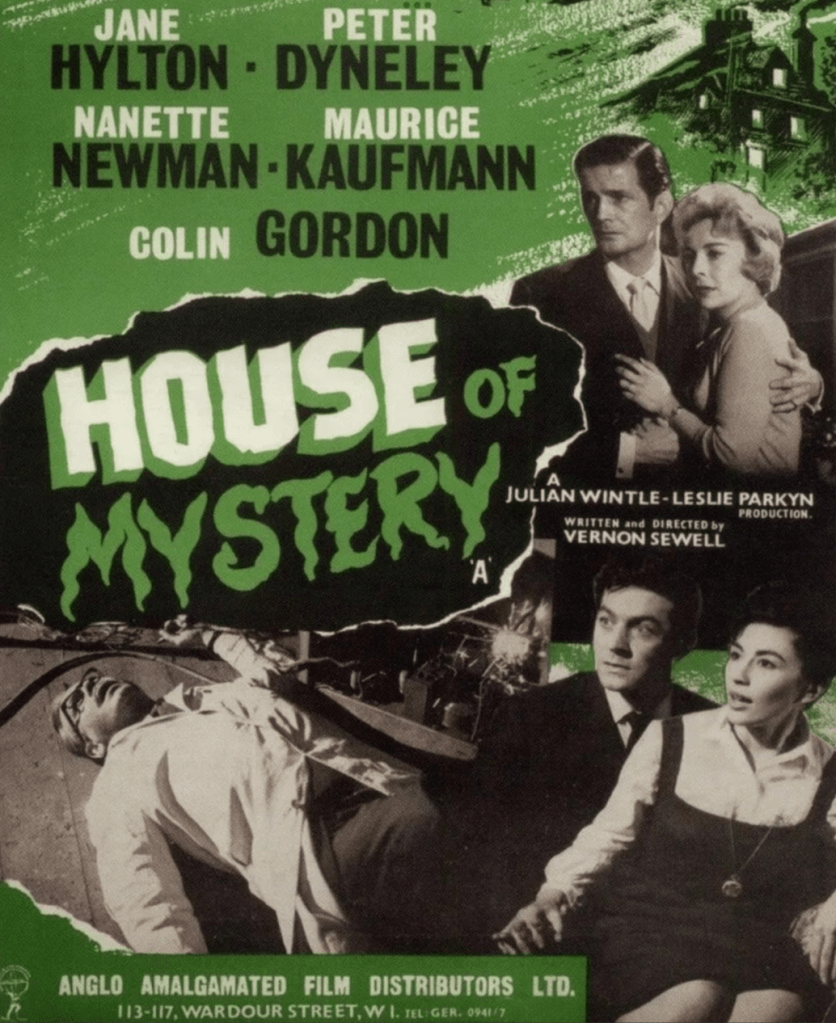

Poster for House of Mystery (1961)

Vernon Sewell had already made three versions of stage play The Medium by the time he had another go with House of Mystery in 1961, but let’s be glad he did. A pre-The Stone Tape riff on the concept of residual haunting, it’s mostly made up of flashbacks, and while the central mystery and final reveal are not exactly subtle, they are still effective, as is this rather wonderful little film, and it does it all in under an hour.

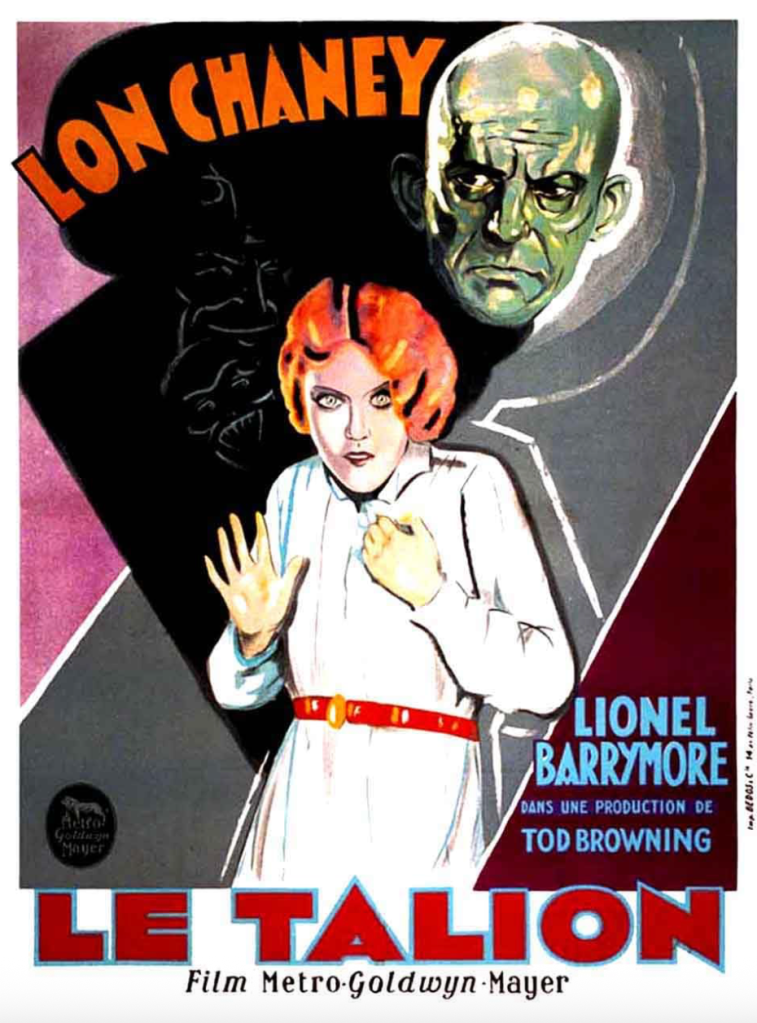

Promo image for Murder by the Clock (1931) and poster for The Unholy Three (1930)

Murder by the Clock, directed by Edward Sloman in 1931, is a macabre early talkie mystery thriller that has some of its stage-trained cast playing to the cheap seats with the advent of sound, but benefits from Lilyan Tashman having a blast as a scheming seductress after an inheritance. It also has an old, dark house (and graveyard!) setting, crypts, secret passages, murders and a flinty, blackly funny heart.

The Unholy Three, directed by Jack Conway in 1930, remakes a Tod Browning film from only five years before, starring the same leading man, and sticking to the same story. Why bother? Well, this was the talkie debut of Lon Chaney, so a real event, and what better way than a story he knew and the audience already loved. Sadly, it would turn out to be his only talkie, and his last film, with Lon dying a month after The Unholy Three‘s release. We have just this one to go on, but it’s pretty clear from it Chaney’s career would have survived the transition to sound. He’s incredibly good in this, his performance charismatic, captivating and showing that he understood the new opportunities for film ahead. Lon Chaney is one of the greatest actors from the entirety of cinema history, and as a swan song for possibly the best to ever do it, The Unholy Three, and its final scenes, is pretty much perfect.

Television

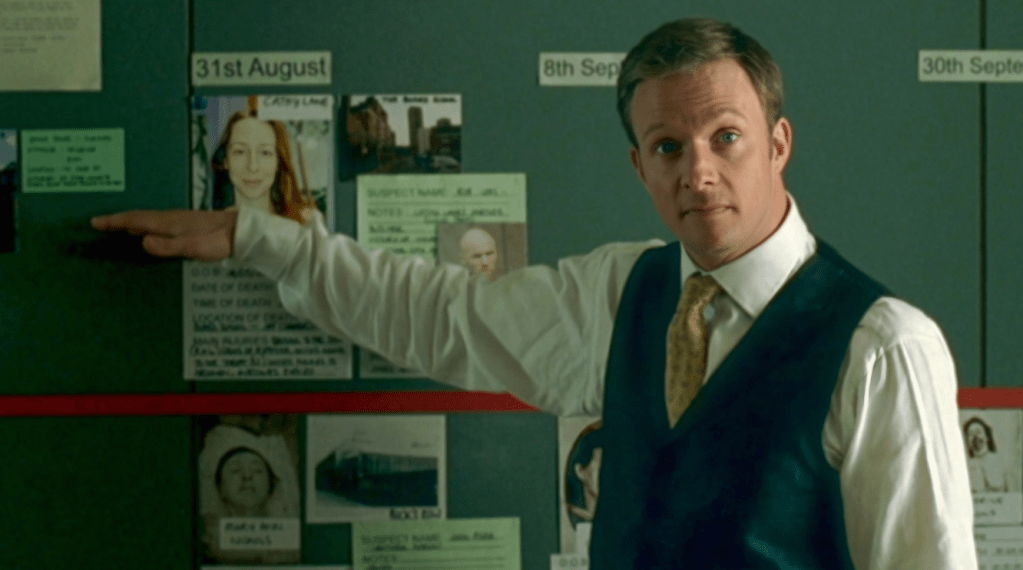

Detective Murdoch and Doctor Ogden. And a brain.

Highlights this year have been the always revolving schedule of shows like You Bet Your Life, The Jack Benny Program, Law and Order: Criminal Intent, The Twilight Zone, One Step Beyond, Dark Shadows, Upstairs, Downstairs and more, but the most surprisingly enjoyable experience has been a late-in-the-year start of Canadian detective series Murdoch Mysteries, based on the novels by Maureen Jennings, and currently at 19 seasons. Season one has had Murdoch meet Arthur Conan Doyle amongst others, alongside showing his fascination with the future of crime solving (‘finger marks’, lie detectors, forensic science). It’s all agreeably easy-going, but not undemanding, entertainment.

Books

Covers for The Story of Victorian Film and The Silent Film Universe

Two excellent early film histories were published this year, and both combined scholarly insight with accessibility and a passion for the beginnings of cinema, establishing themselves almost immediately as key texts. Bryony Dixon’s The Story of Victorian Film and Ben Model’s The Silent Film Universe are essential reading for anyone who wants to know how we got from there to here, and why these eras of film are full of life and innovation and ever vital to explore.

Cover of Hollywood: The Pioneers

Kevin Brownlow had already written one of the definitive histories of silent film with his 1968 book The Parade’s Gone By… but just over a decade later, he did it again, this time putting together the definitive documentary on silent film, the 1980 Thames Television series Hollywood. The accompanying, highly recommended book wisely doesn’t try and retread his previous work. Instead, Brownlow collaborates with another film historian, John Kobal, to create a book that is equal parts informative text and beautifully done visual history, full of hundreds of often rare photos. You can find this for about £5 (or equivalent in other areas), so very much worth it.

Covers of Fleischerei and Phengaris

I’ve written about both of these books already (Modern horror writing at its best) and they remain two of the best pieces of fiction of the year. If you haven’t already read them, you really should.

Music

I’ve gone from being obsessed with music a couple of decades ago, to barely registering what is happening with it these days, so probably good for me that two favourite bands released their new albums this year, Deafheaven (Lonely People with Power) and Greet Death (Die in Love). Better still that both show each band at their peak. It’s been largely either very loud explorations of losing humanity in the lust for power (Deafheaven) or deceptively pretty explorations of the darkness and beauty of life (Greet Death) and I’m grateful for both of them.

Covers of Lonely People with Power and Die in Love