Returning soldier Harry Spalding is determined to uncover how his brother died in the remote Cornish village of Clagmoor Heath. Was it the Black Death, as the locals fear, or a more melancholy and human evil?

Generations separate us as people and families and communities. Sometimes were decades, centuries or even millennia removed from other humans that walked and talked, loved and felt deeply, bled and lived and died. I contend we’re not so different in what we want, despite the years and the different focuses of each successive generation, the cruelty and petty prejudices that threaten to consume us. We want happiness, however fleeting, human connection, status, safety, love. Those who reached adulthood in the most recent two decades can easily be forgiven for feeling as though the doom and gloom of these years is unprecedented. Growing up in the shadow of a global financial crisis, austerity, a monstrous pandemic and institutions run by the very worst of us is enough for anyone. It’s not that long ago however, that people grew up in wartime or in the feverishly imagined ever-present shadow of a mushroom cloud, or the devastation wrought by AIDS. No, we’re really not so different. And so it is with the art that touches us. The methods may differ, but the intent is similar. To connect, to inspire, to share what it is to be human in all its failures and glories.

My main aim here is to explore how this unusual Hammer classic offers commentary and a caution on the ways we can be toxic and poisonous if we stew in the unspoken, choosing to live in darkness, letting fear control us. The characters in this film are from a time older still than when the film itself was made, but the connection is universal. There are other readings of the film and I recommend you seek those out, too. But first, some context.

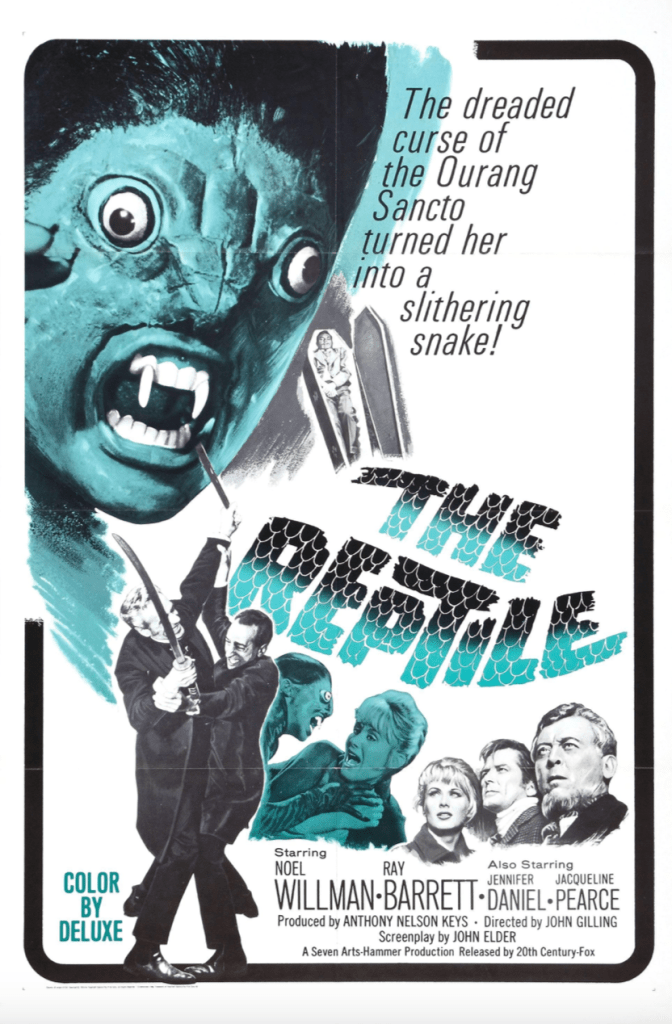

Part of Hammer’s fascinating 1965 four-film cost cutting exercise, The Reptile (UK, John Gilling, 1966) was shot on the same sets as The Plague of the Zombies (UK, John Gilling, 1966) and the only one that actually came in under budget. These films are close siblings in other ways, from mood to intent. Both are Hammer chillers that don’t rely on the tropes of traditional monsters or previously filmed titles. Each is unsettling and compelling in its own way, a mix of mystery and for-its-time grisly and grotesque horror. Gilling, who had a reputation as someone who did not suffer fools, was a tight craftsperson, in charge of the material, pacing and clarity throughout the majority of his work and yet who also includes flourishes of artistry in almost everything he made. And so it is with The Reptile, a film which retains control of its central mystery and also loads it with sinister atmosphere, disturbing imagery and an understanding of the mechanics of what horrifies in sometimes startling ways.

We have no bloodsuckers or traditional monsters here. The horror is not overtly sexualised like Hammer’s vampire films, nor is there anything murderous or of human malevolence in what transpires. Instead, we have a tragedy of family played out where the monster is us. And the deaths are grim in a way Hammer rarely was, to some degree prefiguring the following decade’s obsession with body horror. It’s partly this which provides The Reptile with a remarkably oppressive atmosphere. Much of Hammer’s output of the decade revolved around things rational people can easily discount, from vampirism to monstrous doctors building people out of body parts to zombies, ancient curses and Satanism. These now frequently come as a cosy, distanced horror, one that can be resolved in under 90 minutes and pose no real threat to us. And while the ending of The Reptile doesn’t stray too far from this template, the majority of the film is something else. The deaths in the film are, well, disgusting. Each victim starts frothing at the mouth, turning black, their bodies dying from poison. Still recent world events have only underlined the fear that can be generated by something invading us, free from any moral underpinning, indiscriminate. This is how events first appear in Clagmoor Heath with people dying and the community circling in on itself in fear. And fear and poison are key themes of the film, both viscerally and brutally swift in the deaths and achingly sad in the central relationship between Dr. Franklyn and his daughter. A fear and poison that affects not just them but spreads out into the community they live within.

Harry’s brother Charles dies as the film begins, the prowling camera showing him stalked by something through the countryside until he is cut down and left blackened, rotted to his core. Harry meanwhile has a new wife and nowhere to stay. It’s partly this that brings him to the village, inheriting his brother’s house and giving the new couple somewhere to live. But there are also unanswered questions about his brother’s death and Harry has decided he will find out what really happened. It’s not long before Harry has artlessly alienated the suspicious villagers even further and only friendly(ish) publican Tom remains (played in an expanded role by Hammer cameo master Michael Ripper). In the course of his investigation, Harry comes into contact with the profoundly unfriendly Dr. Franklyn, who has more reason than any to seek the solitude that comes from living on the heath. That Franklyn leaves flowers on Charles’ grave underlines to us there is something rotting the doctor too, a poison of a different kind, one that has destroyed the generations that should have followed him.

The Reptile has many fine qualities, making it one of Hammer’s very best films. It has an unusual (for Hammer) cast, beautiful use of sets and another melancholy and haunted turn from the estimable Jacqueline Pearce. We have John Laurie as a twisted and ultimately deeper and tragic riff on the comic relief character. Gilling does wonders with his budget, producing a frequently handsome film that succeeds as chilling horror including at least one great jump scare. The core mystery is at once obvious and complicated. Don Banks’ score is a wonderful mix of the melancholy, the brash and the inventive. Anthony Hinds’ screenplay (writing here under the name John Elder) is unforgiving and, combined with Gilling’s skill as director, a bold approach for Hammer. The Reptile is a stirring and remarkable tale of curses, disturbed graves, death and desire.

For the rest of this piece however, I’m going to explore that key theme of the film which, for me, keeps it ever-relevant to the now and can resonate with us personally, through its mournful atmosphere, heavy with guilt, to its focus on the damage wrought by those who act without integrity or passion or courage. From here there be both spoilers and commentary you may wish to avoid.

In The Reptile, Dr. Franklyn has returned to England after time overseas with his daughter, Anna. Franklyn and Anna are attended by a servant, known only as The Malay. Franklyn presents a harsh front, rude and dismissive of attempts to converse or connect with him. He is contemptuous of his daughter, cruel and unkind to her. Despite his protests to Harry that he is not a doctor in the way the village needs, no surgeon but instead a doctor of divinity, Franklyn also shows no interest in discovering more about what is killing people. This is because, as the film reveals, Franklyn knows ‘it’ is Anna. In his time overseas, Franklyn took a colonialist’s approach to the secrets of the religions he encountered and one such ‘cult’, of which The Malay is a member, took extreme umbrage at his methods and disregard for what they considered holy. Kidnapping Anna, they placed a curse upon her which sees her turn into a snake creature with a poisonous bite. Franklyn has retreated with Anna to somewhere remote, surrounded by the empty collected trophies of his work and travels, watched over by The Malay, to endure his suffering. And suffering it is, with Anna the victim of his hubris and arrogance, condemned to live not even half a life, no joy in her future. When Franklyn lays those flowers on the grave it is symbolic of the regret, loathing and guilt that is his life now. He has destroyed the life of his daughter, Anna turned literally into a monster to punish him. In Franklyn’s distorted world, those flowers are for him more than anyone else.

As touched on earlier, The Reptile is not a traditional Hammer horror film. Although not new to themes of tragic monsters, notably in pictures like The Curse of the Werewolf (UK, Terence Fisher, 1961), Hammer arguably had its greatest success with the villainy of its Dracula and vampire series. The Brides of Dracula (UK, Terence Fisher, 1960) presents a somewhat more nuanced evil and it’s there in Van Helsing’s mix of pity and disgust at the close of Fisher’s first Count film as Lee’s king of the vampires crumbles to dust, but ultimately there’s no quarter given to wickedness that inarguably must die, must be purged, and in the context of desire, must be contained. Helen Kent’s animalistic panic at her demise in Dracula: Prince of Darkness (UK, Terence Fisher, 1966) followed by the beatific expression on her face after being staked to death makes it clear to us, Dracula and his ilk are no misunderstood monsters, but evil in a pure, defiling form. After all, it’s part of the enduring appeal of certain horror stories, as with the police procedural, where equilibrium is disrupted by evil only to be restored at the end. But there is no restoration at the end of The Reptile. Undeserved tragedy begets yet more tragedy and no one is left untouched. Fire is so often used at the conclusion of a film as symbolic of a cleansing, the world being reset. Here it just covers the truth, burying everything unspoken in ashes, cleansing nothing.

This then is a key theme of The Reptile for me. How recoiling from acknowledging and confronting ourselves, our personal guilt and regret, if left denied, often reaches out beyond us to others, impacts on the lives of people we care about, usually first and most profoundly those we share blood or bonds with. About how our actions reverberate down the years, how that poison infects others and spreads like a death that consumes. Franklyn tries to hide, to disappear, to run from and ineffectively reduce the damage his actions have caused but not try to fix it, to refuse the help he is desperate for. Instead, he acquiesces to self-inflicted punishment, wallows in his misery, gives up on his daughter and anything she might want from her life. And yet the guilt will not leave him be. It dismantles everything around him, even as he tries to stumble on and blank it, unravelling anything he touches. He lives in fear of himself, what he has done, and what will come next as a result of his inability to act.

This can be found in The Reptile in its approach to fear, from fear of ourselves, or feelings for each other and more widely of those we meet and subject to fear of the other. The Reptile is uncommon in its time in that its fear of the other is not presented through overt racism or xenophobia. The Malay is not a cartoon villain here, but instead an agent of revenge without comment as to whether that revenge was earned or justified. Hinds’ writing is thoughtful and subtle here when compared with some contemporaries. The curse placed upon Anna is not The Malay and his people acting with eye-bulging, moustache-twirling malevolence. It is, for him and his people, simply a matter of justice. Instead, the other presented here is a different kind of fear, a fear of ourselves and the people, even in our own immediate family, that we know and love but can never really know but also in how we choose not to acknowledge who we are and what we have wrought. It’s presented in how Franklyn is at once appalled by and desperate to protect his daughter, but only really to hide his shame.

Anna is a victim, cursed through something she did not bring upon herself, by the action of one who should have been building a world she could find her place in. Here she is confused and lonely and unable to explore her dreams or desires. This is all instead directed at her uncomprehending father who it seems would be equally uncomfortable with the idea of his daughter maturing sexually as he would be her turning into a snake monster. It’s both symptomatic of the time it is set in, but particular to Anna and the life Franklyn knows he has doomed her to. We can imagine Anna’s wants and her desires have never matter to Franklyn until he was confronted by them. Franklyn’s cowardice as a human-being swirls at the centre of The Reptile, as much as his self-involved guilt and grief that she has no real future. These are the layers here to unravel how it remains so devastating nearly sixty years later. In that respect, this is as potent a metaphor for the fears of the parent about what the child may become and learning to love who they are as The Exorcist (US, William Friedkin, 1973). Except here, Franklyn knows what Anna is and why and there is nothing to love for him, a mirror showing him his failings.

For Franklyn, the poison is of his own making. Anna is a mirror too, to his crumbled hubris and it is fitting, for him at least, that he dies at her kiss, a kiss as poisonous as he deserves. And there is The Reptile as cautionary tale against our hubris, selfishness, disinterest, arrogance and living in fear. We might want to, but we can’t hide from that which will consume us, and sometimes those we care about. If we really do care, we must force ourselves to confront the darkness, if not for us, for those who, like Anna and the people of Clagmoor Heath, don’t deserve to share in desperate things not of their making.