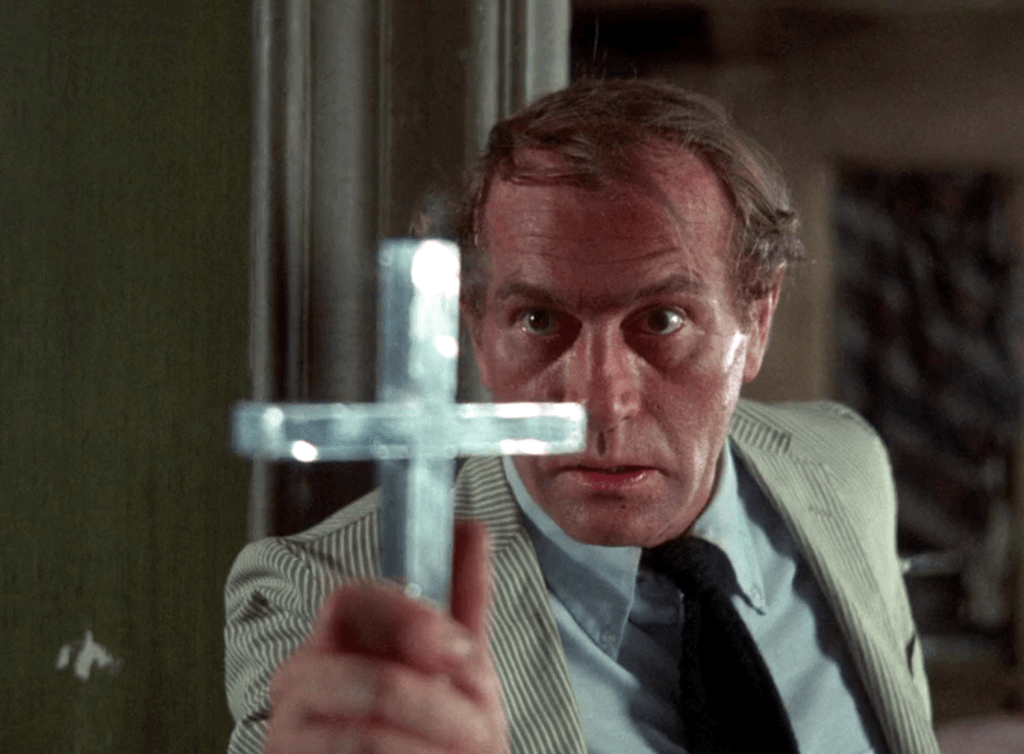

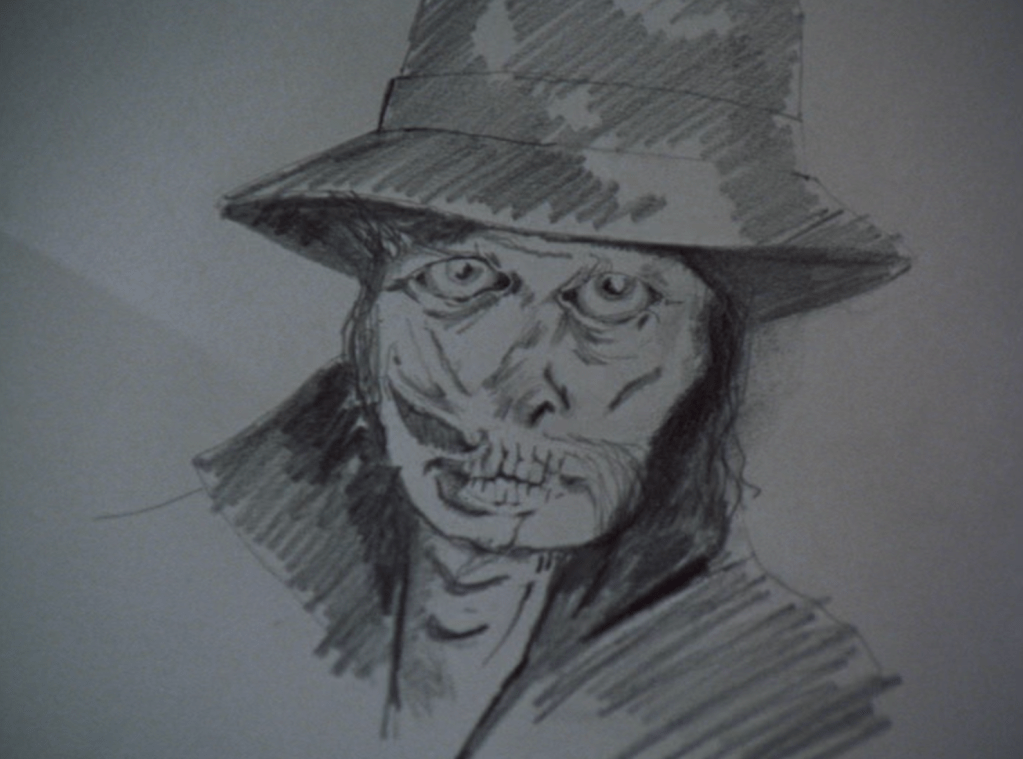

It’s my esteemed and correct opinion that Carl Kolchak is one of popular culture’s greatest characters. As brought to life by Darren McGavin in a shabby seersucker suit and straw hat, he’s a lovably shambolic, rough-edged crusader for the truth. The reporter started out life as the main focus of Jeff Rice’s novel The Kolchak Papers. It tells of a foul-mouthed drunk who had a remarkable story to tell about a vampire loose in Las Vegas, who used Rice to get his story out. As he was working unsuccessfully to get the book published Rice was also inking deals with those who could put his story on the screen. This was the early 70s and television movies were a huge deal, bringing in massive audiences. So when ABC optioned the book you can imagine Rice’s excitement at the prospect of bringing Kolchak to homes all across America. Ultimately it would be the hugely talented Richard Matheson who would write the script, slightly softening Carl’s gruff edges but keeping the humour and commentary that pops off the pages of Rice’s book (I don’t think Stephen King was a fan, however).

Dan Curtis was onboard as producer and it might be hard to get just how big now, but Curtis’ previous project Dark Shadows which had finished in 1971 was huge. It turned the reluctant Jonathan Frid into an unlikely middle-aged sex symbol and had a generation of monsters kids running home from school to follow plots of vampires, werewolves and all sorts of supernatural chicanery taking place.

John Llewellyn Moxey was brought in to direct and in early January 1972 Carl made his screen debut. It was a smash hit and brought in the biggest ever audience for a TV movie at the time. There’s a reason it was a hit: it’s near perfect, a mix of serious scares and humour centred around McGavin’s effortlessly charming performance, ably supported by Simon Oakland as his suffering editor Tony Vincenzo. At first here Kolchak is a beat reporter, using his police scanner to show up as quickly as possible at crime scenes and generally making himself a nuisance to the powers that be.

When young women start turning up murdered, Kolchak thinks he’s got a killer on the rampage, but soon he finds out this killer might not even be human. Carl’s the type of guy who goes where the leads take him and so when the pieces start to fit that it’s a vampire that is killing these women, Carl thinks something must be done. Those powers that be aren’t buying it and they set about making Kolchak’s life even harder work. But that’s not going to stop him getting to the truth and doing what it takes to stop the bloodsucker from getting away with it. The thing about Carl is that he believes the people have a right to know and he’ll protect that right no matter the cost to himself. It’s not that he’s particularly noble, it’s more a compulsion that truths hidden should be revealed. If you haven’t ever enjoyed this classic go and find it now.

When The Night Stalker was a huge hit, inevitably talk of a sequel followed. That talk turned to action in double time and in 1973 The Night Strangler followed this time directed by Curtis. In this one Kolchak has relocated (not through choice) to Seattle and comes into contact once again with a despondent Vincenzo. At the same time another killer is murdering people by strangling them (but of course) and using their blood to stay alive, something they have been doing for over a 100 years. Kolchak discovers the truth but again narrowly avoids getting killed for his troubles and is railroaded out of town for good.

The same year Rice finally got his novel published as a tie-in to the first film. A reverse of the first film’s process next year found Rice adapting Matheson’s Strangler script for a tie-in book that would be published in 1974, the same year the series started. Before that Kolchak had nearly made it into a third film, in a script by Matheson and William F. Nolan called The Night Killers which would have had Carl in conflict with android replicas. McGavin was tiring of the formula and didn’t want to do it. Curtis wasn’t apparently impressed either and things cooled for a while, during which Curtis and Nolan went off to do spooky TV movie The Norliss Tapes, which could easily have been a Kolchak case.

Eventually after negotiation, McGavin was tempted back for a weekly series which he could produce, although Curtis was finished with it and opted out. In September 1974, after multiple protracted negotiations and fallouts, and in a season ABC desperately needed success in, Kolchak: The Night Stalker hit small screens as a weekly show. The first episode was ‘The Ripper’, and it finds Carl now set up in Chicago, still working for Vincenzo. It’s almost a remake of sorts of the two films with its story of a madman killing people off who turns out to be THE Ripper, a maniac of unusual longevity.

Like many an episode of Kolchak it has its good and bad elements. Plotting in the episodes is frequently perfunctory, low budget monster-of-the-week stuff that holds few surprises. But the series still had it’s star in McGavin and he’s reliably excellent no matter if he’s being chased around a cruise ship by a ‘werewolf’ who resembles more a guy who fell face first into some hair-restorer as opposed to a beastly lycanthrope, or sowing a zombie’s mouth shut and hoping it’s not going to wake up while he’s doing it. There’s many reasons to love McGavin but there’s a great little moment in ‘The Ripper’ where you just know he’s doing it the way you would too. Trapped in the Ripper’s room all Kolchak has to do is stay quiet and he’ll make it out unseen. But when the Ripper gets too close Kolchak lets out a yelp and makes a run for it, blowing his cover. By grounding Carl in recognisable flaws and humour, he became more real to us. Not an impervious hero but instead a dude who’s scared shitless but can’t turn away from the truth or doing what needs to be done.

When you go back to the series now one of its strengths is just how infrequently it chose to stick with the usual screen horror villains. Sure, there’s the Ripper and a werewolf and another zombie. There’s even another vampire but it links in with The Night Stalker in an interesting way and is one of the best episodes. But others included witches, prehistoric monsters, a haunted knight’s armour, robots, aliens and demonic spirits. This level of creativity always fought against the network drive to make every week’s entertainment broadly the same as the week before and is representative of what eventually brought the series down before it’s first season had finished, with a few scripts un-produced. Ratings were never massive and as the series went on McGavin got restless and the network could see it was not the hit they hoped for, with the various attempts at meddling causing friction between star and studio. In 1975 the episode order was cut by two and Kolchak limped to a sad end. But it was not the end really.

Reruns of the series would find more receptive viewers in the late 70s and this would continue through the 1980s until the series found a new home on the cable Sci-Fi Channel at roughly the same time a new series called The X-Files on Fox was moving from cult hit to mainstream sensation. Chris Carter has spoken before of his memories of Kolchak in part inspiring Fox Mulder and Dana Scully’s adventures and this helped continue to build an interest for newer viewers as to who this Carl Kolchak was. Home video releases of the first film and series started to surface too, along with the reruns allowing people to get to know McGavin’s intrepid reporter again. Mark Dawidziak, a critic for an American newspaper, wrote a guide book on Kolchak that arrived in 1991 called Night Stalking: A 20th Anniversary Kolchak Companion. This led in turn to a new deal between Rice and the same book’s publisher for new Kolchak novels. To kick it off Dawidziak was tasked with writing the third book (to follow on from the films and series) and Grave Secrets duly arrived in 1994. The deal for more faltered when the publisher was unable to actually get anything else in print and nothing more would arrive for some years. But thanks to Dark Shadows actor Kathryn Leigh-Scott’s publishing company Pomegranate Press an updated and now illustrated 25th anniversary edition of Dawidziak’s definitive book would arrive in 1997.

After this, the new century found Carl in surprisingly good health. Universal released a (sadly totally extras-free) box set of the entire series. The two TV movies came out on a dual disc release. A book with Matheson’s three scripts (including The Night Killers) was released with introductions by Dawidziak. Moonstone Books began publishing comics based on the character in 2003 and these became almost an industry in their own right, covering Kolchak through comics (with adaptations of the first film and unfilled scripts), novels and short story compilations. More comic adventures have followed.

In 2005, a short-lived revival series aired starring Stuart Townsend as Carl in an updated version taking in modern TV’s story-arc concerns. Low ratings and inevitable but unfair comparisons to The X-Files did for Night Stalker after only 6 episodes were aired, but it’s a remarkably good and interesting series in its own right. Frank Spotnitz was show runner and took influences from the original but filtered it through a style more influenced by Michael Mann that left us with an unfinished show that is significantly more interesting than its reputation suggests. It’s not all been good news. Back in 2012 Disney announced a film adaptation was in the early stages with Johnny Depp as Kolchak and Edgar Wright directing. This (with or without Depp and Wright) turned out to be just an idea and so far Kolchak has yet to return to the screen. Perhaps this is for the best, given the debacle of Depp’s Dark Shadows film and…you know…everything else.

But if his history has taught us anything it’s that Carl is a tenacious sonofabitch and it’s likely we’ll have him back on the screen someway, somehow. For now though, if you haven’t yet had the pleasure, go find The Night Stalker and get introduced.

(Recent years also found the original films and series getting American Blu-ray releases, another resurrection for Carl)

Further suggested reading:

The Night Stalker and The Night Strangler by Jeff Rice (published variously as separate books and a one-volume compilation)

The Night Stalker Companion by Mark Dawidziak (Pomegranate Press, 1997)

The Kolchak Papers: Grave Secrets by Mark Dawidziak (Cinemaker Press, 1994)

The Moonstone Books various comics, graphic novels, short story compilations and full-length novels.

Progeny of the Adder by Les Whitten (Doubleday, 1965). This is a book at some points rumoured to have ‘inspired’ Rice as it tells the story of a modern vampire terrorising a city (in this case Washington DC) and the desperate attempts to stop the killings.