Recent horrific film and television highlights

Times are tricky right now, but in amongst everything that might be going on, there’s plenty to enjoy. I get a genuine distraction from the carousel in my head from a good show or film, very often horror, science fiction or mystery. A meditation of sorts. Here’s what I have enjoyed across the past few weeks or so.

(A warning: There’s no serious, deeply analytical reviews here, so abandon all hope if that’s what you are after. I’m not writing an essay. No spoilers either. You’ll get a brief summary or introduction and one or two things from each I enjoyed.)

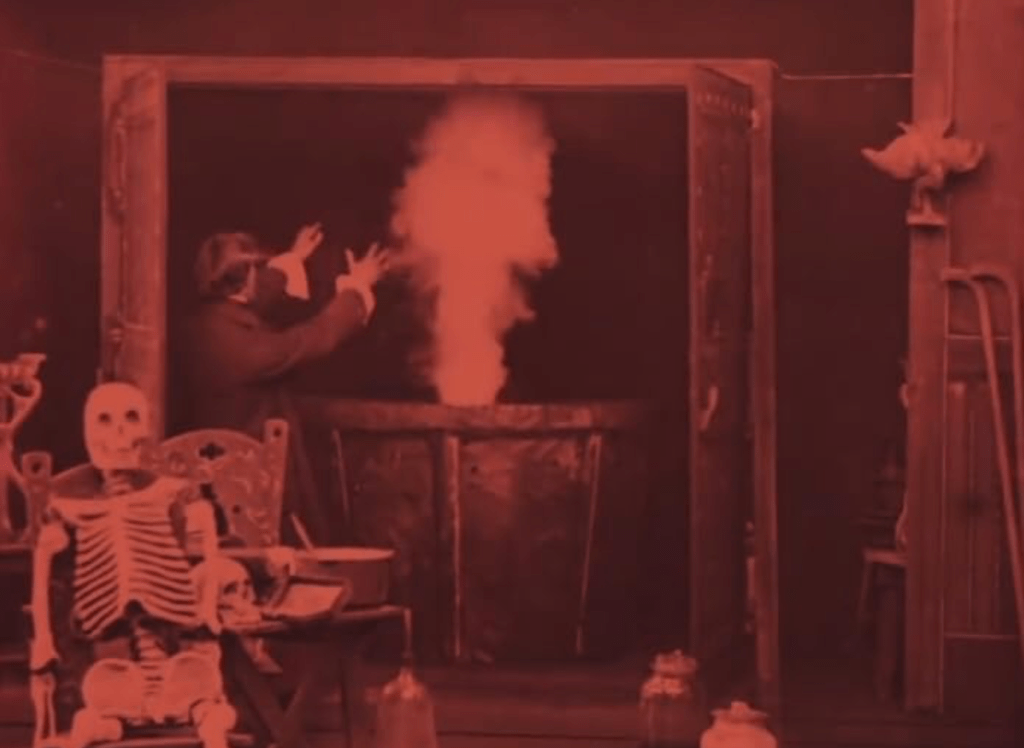

In 1910, J. Searle Dawley wrote and directed a one-reeler adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. It runs to about 16 minutes, so is only a swift tour through the beats of the story, but manages to generate empathy for the monster, poisoned by Frankenstein’s arrogance and hubris. The birth of twisted life sequence itself is quite a startling example of early cinema’s ingenuity. This monster is formed of fire and potions in a bubbling cauldron in an effect that, while basic, conveys the pain of its forced creation. It’s remarkable, and an enduring example of early filmed horror’s ability to captivate and even appal modern us, with all our ‘sophistication’.

Sweet, Sweet Rachel (1971, dir. Sutton Roley) was writer Anthony Lawrence’s pilot-film-of-sorts for the following year’s The Sixth Sense (1972), his phenomenal, egregiously short-lived ESP-themed television series that starred Gary Collins. The film follows a similar approach, telling of Rachel, haunted by visions of death. Dr. Lucas Darrow, an ESP expert, tries to help her unravel what is happening to her as her grip on sanity wavers. Like the series, what works so well with Sweet, Sweet Rachel is its absolute lack of fucks given to anything but its own internal logic and its focus on a nightmare flow to events and imagery. The central mystery is nicely loose, and if you enjoy it, I shouldn’t need to do anything else to convince you to seek out The Sixth Sense series, one of television horror’s weirdest, most underrated gems.

Art Wallace is probably most well known as the developer and principal writer of the earliest days of television classic Dark Shadows (1966-1971). A decade or so later, Wallace had two attempts at an occult detective series, with pilot films The World of Darkness (aka ‘Sentence of Death’) in 1977 and The World Beyond (aka ‘The Mud Monster’) in 1978. The magnificently named Granville Van Dusen plays sports journalist Paul Taylor. After dying for two minutes following an accident, Taylor is ‘gifted’ with the ability to see ghosts, who nag him about people in danger he must help but without, you know, any real details or anything that might assist him. In these films, that includes a woman trying to unravel the mysterious deaths afflicting her wealthy, messed-up family, and an island stalked by a golem. There’s nothing new in either, but they’re both so stylishly, sincerely done that doesn’t matter at all. The first film’s elegant, dark chills give way to the second film’s oppressive, relentless focus on visceral experience, but both pack in actual horror and are great fun for people who love ponderous, deliberately paced 1970s television horror (that’s me).

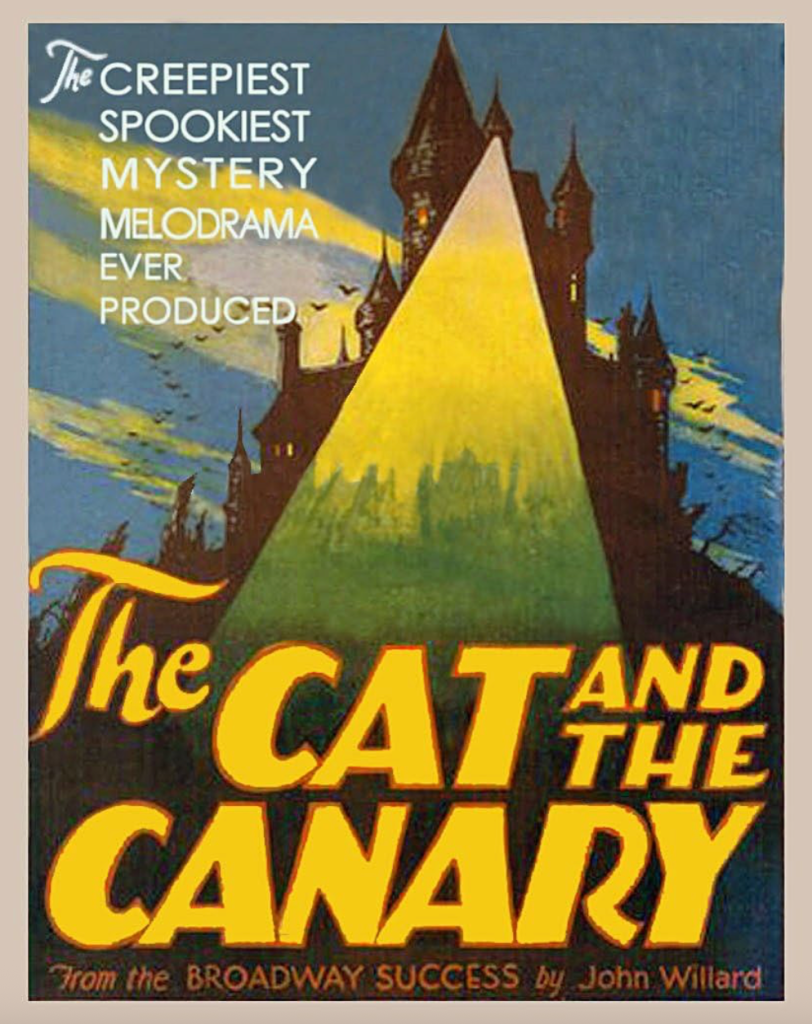

The Cat and the Canary (1927, dir. Paul Leni) was one of Universal’s big early horror successes (before the run we have come to associate starting with Dracula in 1931). Like many a film of its time, it was based on a stage play, a darkly humorous thriller by John Willard, but the masterstroke of bringing in the director of Waxworks (1924) means this is no dusty, static retread. Rather, Leni and cinematographer Gilbert Warrenton make a virtue out of its isolated, minimal locations, the lack of dialogue in a silent film (via intertitles), and employ various German Expressionist techniques to create several sequences of gorgeously fluid, alive and confrontational film. A lot of the tricks – sliding panels in walls, disappearing bodies, reappearing corpses – are all too familiar now, but in 1927 they weren’t; this was still fresh to movie theatres. It’s a comedy horror that achieves that rare balance between being genuinely amusing and yet ruthlessly serious in its chills. Really fucking good.

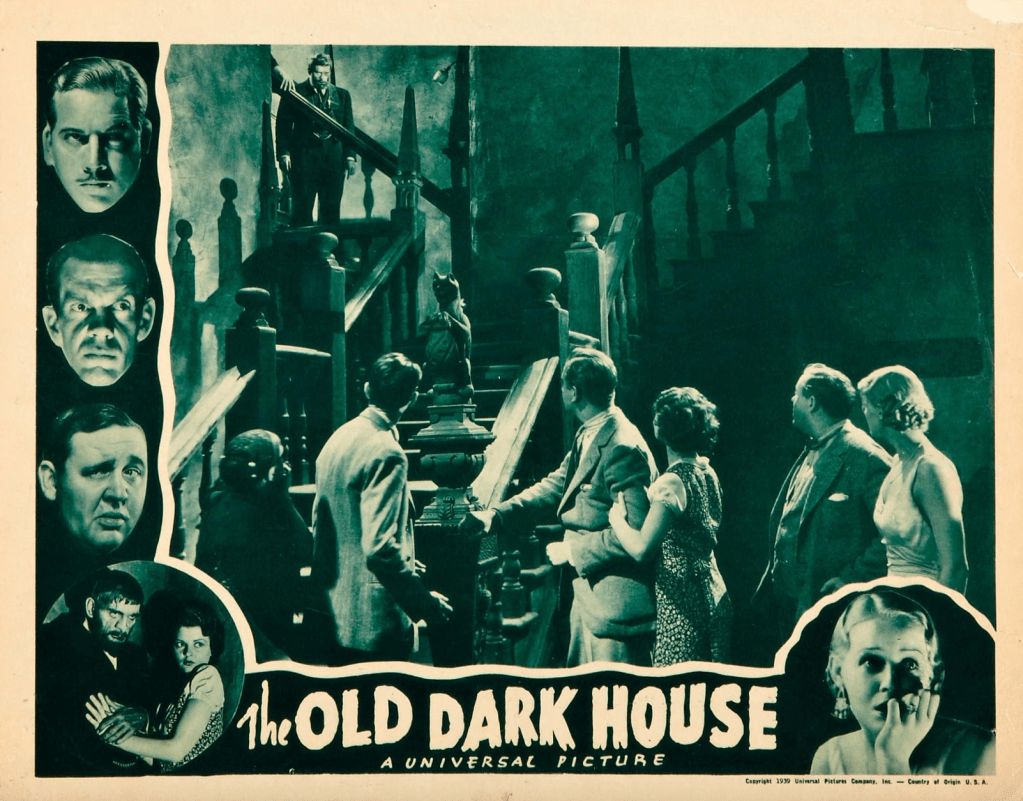

James Whale followed the cadaverous, scandalous Frankenstein (1931) (we’re not counting The Impatient Maiden, his intervening drama) with The Old Dark House (1932), a tale of several people stranded by a violent storm and forced to seek refuge in the titular home, its inhabitants very possibly more dangerous than the rain and thunder outside. If you haven’t seen this, you’re really in for a treat, and you should fucking watch it, now. It’s about as good as films get, and has Whale at the peak of his artistry, directing a pitch-perfect cast. A Pre-Code classic,The Old Dark House is as dangerous, raucous, and subversive now as it was nearly a century ago. It’s funny, moving, genuinely unsettling, gleefully out of step and defiantly queer in the more-than-one meaning that word carries.

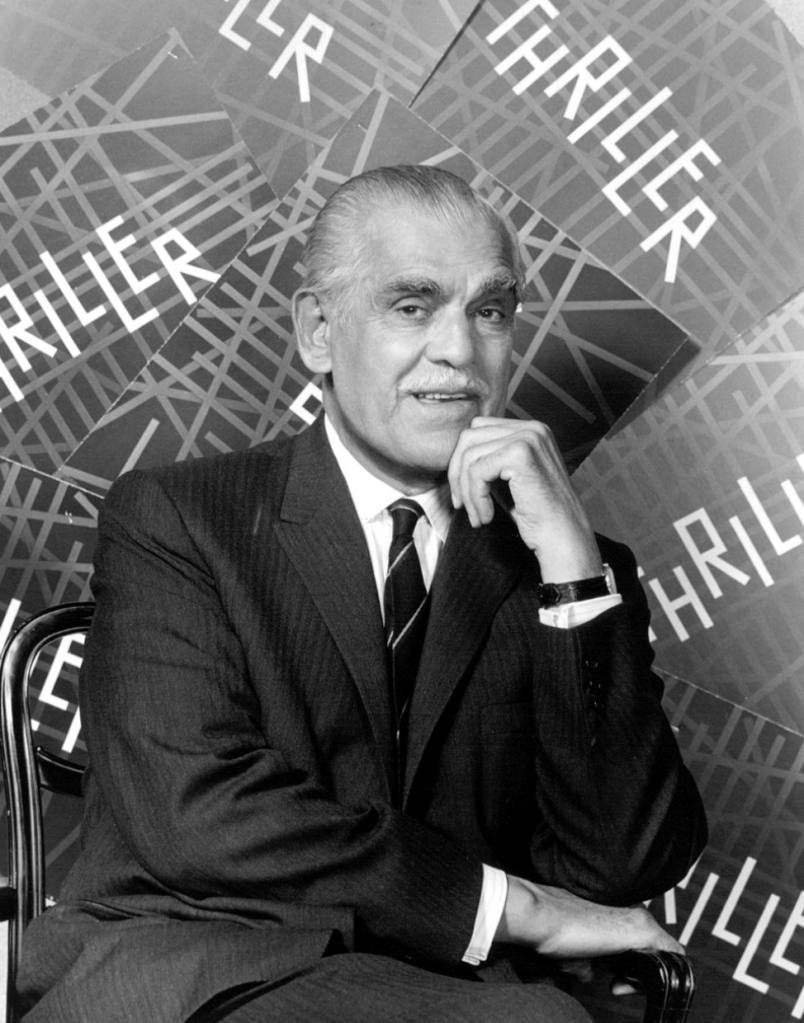

In Danse Macabre, Stephen King’s 1981 history of horror, he suggests Thriller (1960-1962) was the best spooky series of its kind ever shown on television up to the point he was writing and got theWeird Tales vibe right on. He’s wrong.Thriller was in fact wildly erratic, from its early days of slow-moving crime stories, and still in its later episodes King was referring to. Some episodes were good, some were great, some were boring as shit. When it does nail it, the results are sublime, though often not for everyone. If you have a taste for overripe, camp gothic, then season two, episode twelve (‘The Return of Andrew Bentley’) is one such example. Richard Matheson scripts and John Newland directs and stars in a very silly – but very good – story of death and body snatching. To be clear, I really can’t underscore how much almost every bit of this episode is, objectively, bollocks. The score, the shameless performances, the dialogue. The drawn out ending. It’s an arched eyebrow daring you to take it seriously. But somehow, mix it all in together and you have a knowingly silly cocktail of horror cliche that is a lot of dumb fun.

Behind its gloriously garish title, Gene Fowler Jr’s horror-tinged science fiction thriller is a serious movie that plays almost like a lost first attempt atThe Outer Limits (1963-1965), or Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, dir. Don Siegel) if that film was much more mean and obsessed with both the promise and threat of sex and the secrets we can and can’t keep. Marge marries the man of her dreams only to find he changes after they wed, almost like he is a different person. That’s because he is. There’s sci-fi thrills here and gloopy special effects, alongside a genuinely tense, pointed narrative only slightly undercut by one element of its ending. All the better then, that the other elements land so well. A sweaty, supple good time.

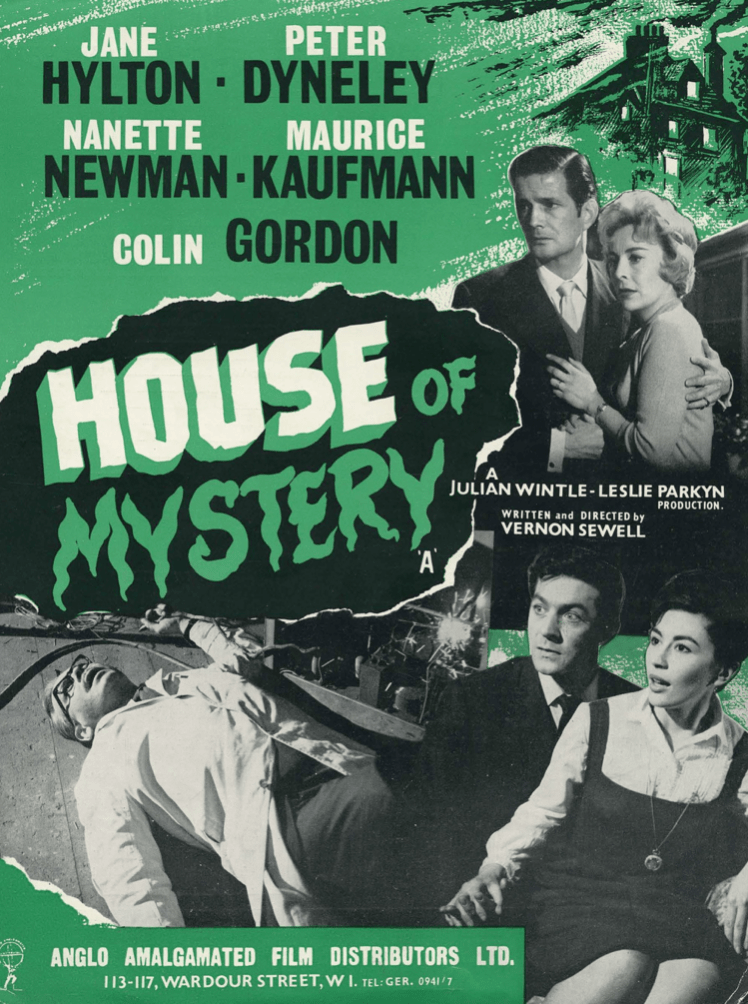

Vernon Sewell writes and directs his fourth go at an adaptation of the playThe Medium. A young couple think they have stumbled onto an impossibly cheap bargain of a house. When the melancholy caretaker offers to tell them the history of its ghosts and murder, they realise why it’s on at a bargain price. Comprised of several smoothly done flashbacks, House of Mystery (1961) is a kind of proto-run at the ‘residual haunting’ theory that Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape (1972, dir. Peter Sadsy) popularised significantly more loudly a decade later. Sedately paced for a 56-minute long mystery, it nevertheless captures and keeps the attention and squeezes in enough specifically British eccentricity to be plenty of fun. A delightful, creepy curio.