You might think everything is terrible right now. You might believe that part of the suck is that there’s nothing new in culture (from films to television, books, music, theatre, art), that we are drowning in remakes and reboots and reimaginings. You mutter curses as you read of ‘a dark retelling of the Pinnochio story, coming to book stores this year’. Dick Wolf wakes up in a fluster one Sunday morning, an idea for a new ‘franchise’ burning feverishly like so much sloshing jock sweat in his brain. A remake of a film you swear is only three years old is announced. “Doesn’t anybody have an original idea?”, you muse. The answer is no, absolutely fucking not. Where, then, is all the good stuff? It’s still everywhere, thankfully. The people you love, the things that fire your imagination, the world out there. There’s lots to enjoy as we spin in space. Some of it is here, too, in the second instalment of Ghoulishly Good Times. Here’s what I have enjoyed across the last few weeks.

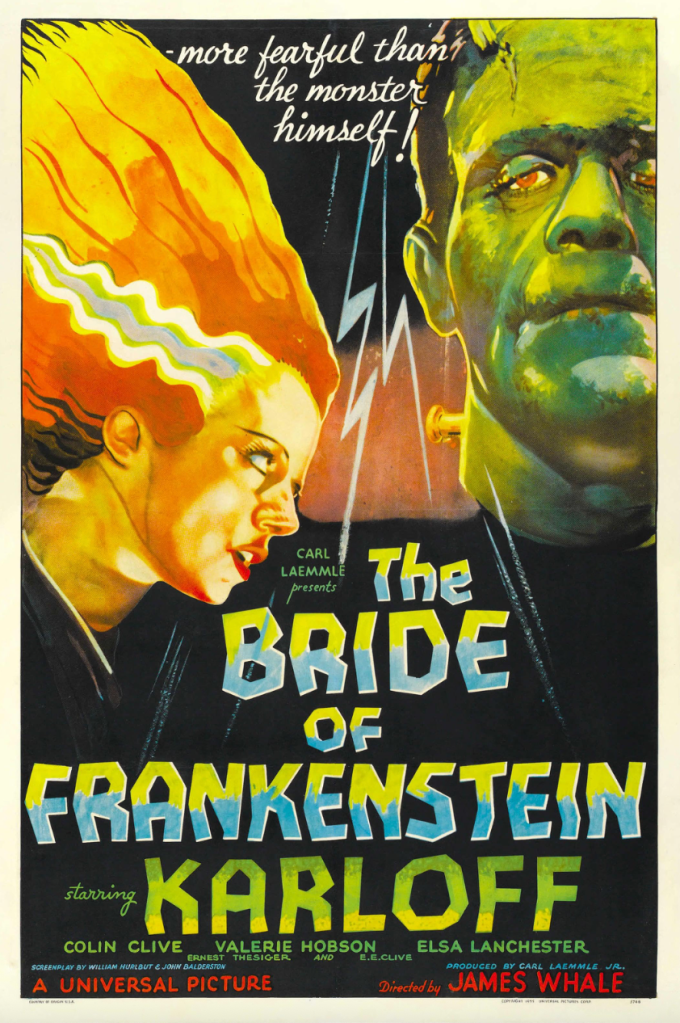

James Whale agreed to take on a sequel to Frankenstein (1931, dir. James Whale) on the condition he could make it a ‘hoot’. And hoot it is, with The Bride of Frankenstein (1935, dir. James Whale) eschewing the gothic gloom of the first film and pitching instead for a dark-hearted fairytale. It carries over the themes of men hungering to play God and brings back Colin Clive as Frankenstein and Boris Karloff as his unloved creation. But otherwise, the film’s messy genesis, going through several scripts and production woes, reshoots and censorship, works to its credit, leaving us with an occasionally coherent series of vignettes that expand the lore, give Karloff more to do, and allow Whale to create something defiantly eccentric. More absurd black comedy-fantasy than horror film, it nevertheless packs in plenty of imagery to compliment the iconic original, and entertains completely.

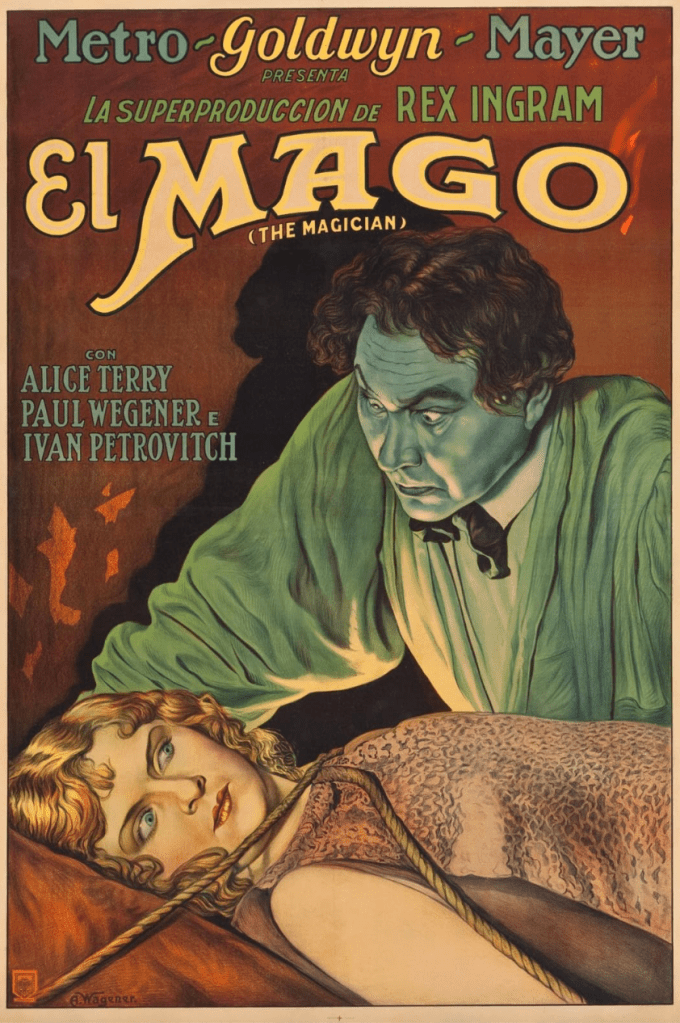

Speaking of Universal’s Frankenstein(s), an acknowledged influence on them both can be found at the end of silent classicThe Magician (1926, dir. Rex Ingram). Gothic laboratories, assistants of a smaller stature, and men playing God. Based on a W. Somerset Maugham novel, the first hour at least finds sculptor Margaret the unwelcome subject of the obsessive Oliver Haddo, hypnotist, magician, student of medicine and all-around bastard (played by real-life bastard Paul Wegener). Haddo is convinced that Margaret is the key to an arcane ritual he has discovered which he believes will give him the power over life and death. Made in France, it’s a beautifully shot, creeping thriller (with some striking location filming) that diverts pleasingly in its final half hour into a gothic horror. Shooting overseas away from studio executive interference certainly helped the film, but at the time, reactions to it criticised it as ‘tasteless’. Take that as a recommendation in my opinion.

Dark Night of the Scarecrow (1981, dir, Frank De Felitta) writer J.D. Feigelson had hoped his supernatural revenge script would have made it to cinemas, but its eventual home on television as a TVM probably gifted the film its legacy. I don’t know what the minor changes made for its new home on CBS were, but there are no edges smoothed. This is a seriously dark, unsettling tale and stands out. A vulnerable man has a friendship with a young girl that upsets local postman and all-round piece of shit Otis Hazelrigg (Charles Durning). He convinces three friends to take matters into their own murderous hands. It’s not long after this that something – some kind of vengeful force – starts causing fatal accidents for the quartet. As events spiral, Hazelrigg moves from disbelief to desperation to protect himself, no matter the cost. There’s lots to love about the film: performances are all great, the atmosphere of creeping dread is nailed from the outset, it’s absurd, blackly funny and shameless about it, and its purposefully slow pace allows director De Felitta and cinematographer Vincent Martinelli space to conjure up some gorgeously unsettling imagery. But the main ticket is Durning, here playing an unrepentant scumbag, a soul black with squalor and hypocrisy, and this film’s dark, festering core.

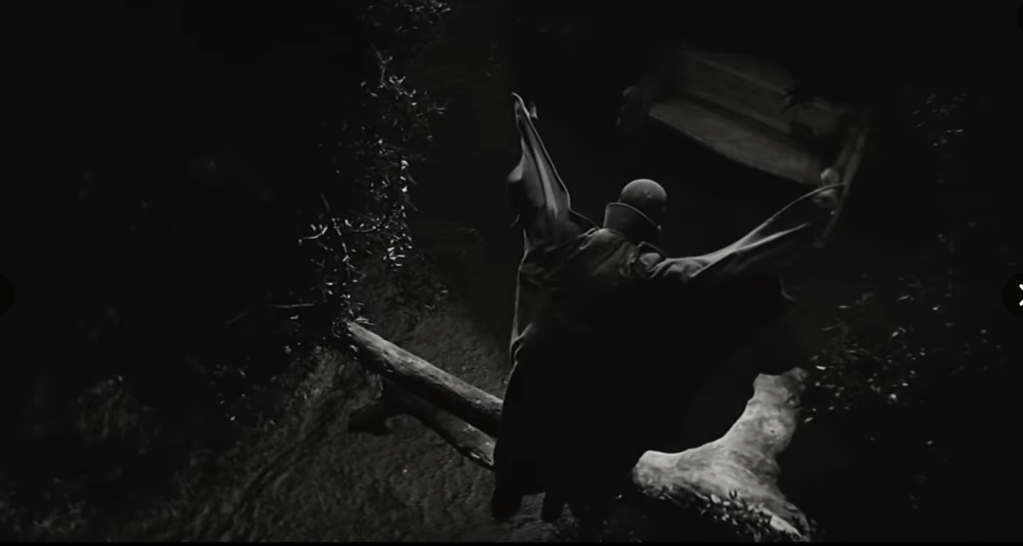

In 1929, Charles Vidor wrote and directed a short film of ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge’, making the first adaptation of the famous Ambrose Bierce story of 1890. It’s only 10ish minutes long but The Bridge (1929, dir. Charles Vidor) plays like a preview to The Twilight Zone (which had its own version of the tale) and similar shows and films. A man escapes his execution on a bridge but his journey to get back to his wife and child is beset by a creeping sense something is not right. Nicholas Bela is outstanding in his role as the man, and Vidor’s version could have been made last week: it experiments with technique and structure in ways that feel familiar to an audience nearly 100 years later. Really very good.

Director Wallace Worsley and star Lon Chaney reunited after 1920’s wild The Penalty on the following year’s The Ace of Hearts (1921, dir. Wallace Worsley), a thriller about a group of anarchists who, having decreed that a rich piece of shit has lived too long, draw cards to decide which of them gets the honour of killing the wealthy prick. Chaney’s Farallone is besotted with comrade Lilith but when she marries their other comrade Forrest, the mission becomes more complicated. Although the mid-section gets a little bogged down and talky (no mean feat for a silent picture), the opening scenes and the tense and beautifully done final sequences more than make up for it. Lilith and Forrest are the nominal leads, but the show is Chaney’s. He gives it his all, and gifts Farallone a tortured humanity that convinces as the film builds to its ending. The conclusion is at once overdone and yet perfect for the movie (more so than the original, which was reshot – in this case wisely – at studio head Sam Goldwyn’s request). Alongside a great Lon, the film’s themes are still heavily resonant today, almost jarringly so. Highly recommended.

The last week has been a tale of three Bats, starting with 1926’s first version of the successful Mary Roberts Rinehart and Avery Hopwood play, The Bat (1926, dir. Roland West). A close relation to the following year’s The Cat and the Canary (1927, dir. Paul Leni), Roland West’s first go at adapting the play is a mix of mystery, comedy and horror that works incredibly well, bringing together a dark house, a cast of potential victims/suspects, and a villain who makes a vividly lasting impression. As with Leni’s film, there’s a lot of German Expressionism influence, some outstanding set design and cinematography, and a finely done balance between mystery, comedy and some genuine chills.

West’s second go came just a few years later in 1930, sound pictures now the standard, with The Bat Whispers (1930, dir. Roland West). West doesn’t appear interested in retreading ground from the first film, and this version focuses more on the mystery element and dialling up the comedy. The Expressionist style is mostly gone, but that doesn’t mean we lose the horror influence entirely. And again, West doesn’t just rehash the first film’s imagery. Instead we get something much closer to the inspiration for Bob Kane’s early Batman of a few years later. We also get a film shot in early widescreen and some ambitious camera work, making use of panning in particular to create some startling sequences. West didn’t get a third go at the title, his career derailed a few years later by a scandal involving the death of his mistress, Thelma Todd, in 1935, a death West was rumoured to be responsible for, though never charged with anything.

The last bat is connected to the original in more than the obvious way and also brings us full circle. Crane Wilbur wrote and directed the 1959 version, The Bat (1959, dir. Crane Wilbur). Wilbur was a contemporary of Roland West and Lon Chaney, adapting The Bat and writing his own blackly comic dark house mysteryThe Monster (1925, dir, Roland West), starring Lon Chaney and serving as a comedic critique of the dark house and mad scientists sub genre tropes and acting as an inspiration for Universal’s Frankenstein films. Vincent Price is in the cast for this iteration, although the horror influence is dropped almost entirely, the focus here on the mystery. It plays like an unusually cynical Scooby Doo episode, and that’s a compliment. The fantastic Agnes Moorehead is part of the cast, too, and there’s some enjoyably unsubtle undercurrents that modern audiences will recognise easily enough running throughout that make it feel substantially different to the previous two versions, and very worthwhile in its own right.