Finding redemption with the festive spirit (and Rod Serling and Peter Cushing)

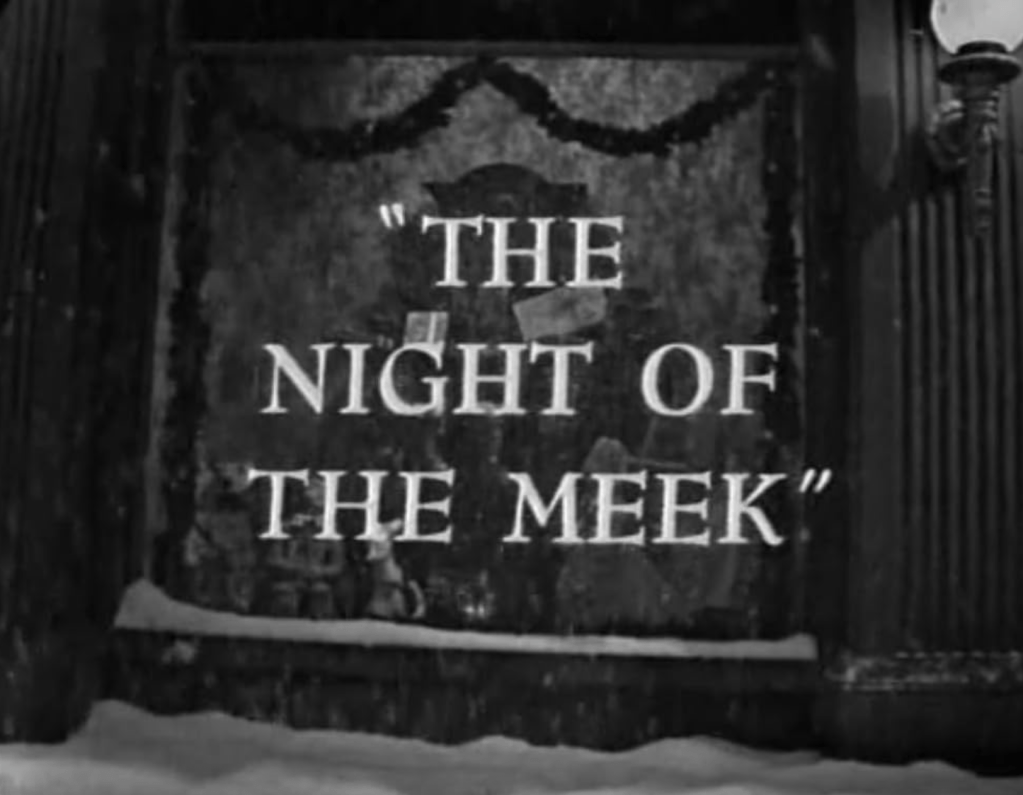

” The Night of the Meek” (The Twilight Zone Season 2, Episode 11)

The Twilight Zone is inarguably one of television’s truly great series. For an anthology show it has a remarkable hit rate. Every such series had its duds but for this show, they are few and far between. Even the weakest episodes have something to them, a line of dialogue or a moment that sparkles. For this writer, Rod Serling is one of the most gifted writers the medium has ever had, and in addition to that was a compassionate person who used his work to connect audiences with their fellow humans, to illuminate the human condition, to encourage us to be better, to do better, to try again. The Twilight Zone often traded in stinging or stirring tales of fantasy, science fiction and sometimes horror. As with many shows, it also had its Christmas-themed episodes and it is one of them, “The Night of the Meek”, covered here.

The macabre in Meek is people. The set up in the episode is following department store Santa and general sad sack Henry Corwin. Corwin doesn’t have much to look forward to other than his next drink. He lives in a ‘dirty rooming house’ and his world is one of hungry children and other ‘shabby’ people just like him. Corwin lives for his Santa routine but the shine has gone out of it. His suit is old and worn and when he shows up too late and drunk with it for his gig, it’s over – he’s fired and ordered out of the store. Despite all of his woes, Corwin muses if he had one wish, it would be for the meek to actually see some rewards. When Corwin can’t even get back into the bar he frequents, he stumbles down an alleyway where the sound of sleigh bells are heard.

In the alley, Corwin comes across a sack that he quickly discovers appears to have magical properties. It produces a seemingly never-ending stream of gifts. Whatever someone asks for, they get. His dream coming true, Corwin starts handing out gifts to the poor kids and down and out men nearby. The episode continues with this mix of melancholic reality and fantastical whimsy towards its hopeful conclusion.

In the episode, people are the worst. Everyone expects and looks for the worst in Corwin because that’s the type of guy they think he is. It’s the type of guy Corwin has come to think he is too, and it’s pretty obvious his idealism and hope is frayed and being drowned in a puddle of cheap booze. Corwin is us – we want to believe in the best of people, but people make it pretty damn hard. Now, Serling had around 25 minutes an episode to do set-up, delivery and conclusion of his stories and so subtlety was not always the prime concern. The characters, Corwin included, are mostly broad sketches, with people like the shop manager Dundee being not much more than functional cliché. They’re ciphers for the point Serling is making about what Christmas can represent.

It can, if we let it, represent good will to each other, hope for the future and the unity such celebrations can bring. If we let go of the hardened cynicism and the weariness, if we let such notions in, even if it’s only for one night we can believe that we’re more good than bad, that’s there something worth saving in us, that we can believe in magic. For many, that’s a hard thing to do in a world, in a world that tells us there’s no magic left, only bleakness and decline. In the time The Twilight Zone was first airing it was only 15 years or so since the end of WW2. It was before Vietnam, race riots, Watergate and innumerable other events conspired to convince even the most indefatigable optimist that we’re on a downward spiral as a species.

That’s not to say things were better then as many things were emphatically not. But it’s for this reason that we should arguably let a little magic into our lives. Believing in Santa Claus might have ended a long time ago for most of us but believing in each other, or that there is some goodness out there, is something we all need these days. And if anyone can convince you to believe in your bones that humans are redeemable, it would be Serling.

As Rod himself puts it in the closing narration “There’s a wondrous magic to Christmas”, so here’s to Henry Corwin and here’s to The Twilight Zone and a momentary respite, a sliver of the brightest light in the darkness of winter.

Cash on Demand

How does Cash on Demand (1961, dir. Quentin Lawrence) evoke a similar joy? Well, it’s not just the ideal Christmas movie but a reminder that, for those of us who might despair at humanity’s worst instincts more days than not, change is possible. Based on the play, it’s the tale of bank manager Harry Fordyce (Peter Cushing), a fussily fastidious man who rules over his branch not so much with a clenched fist but a puckered sphincter. The opening scenes set up the tight-knit team of staff in the bank as they await Fordyce’s arrival. When he does appear their anxious joviality is curtailed and it’s down to the business of money.

Not long after this, André Morell pulls up at the bank, his character Colonel Gore-Hepburn supposedly an insurance inspector but in fact a bank robber. Using threats and coercion, Gore-Hepburn forces the unravelling Fordyce to partake in robbing his own bank. Without giving anything away, the plot twists, new wrinkles are added and tension is ratcheted up. Throughout all this Cushing is wonderfully good, ensuring Fordyce is no cliche and imbuing him with humanity throughout. Morell matches him throughout as the smooth, assured, and ruthless bank robber.

Cash on Demand is a twist on A Christmas Carol. Fordyce might not be the wicked man Scrooge was, but he has forgotten what makes a person. He’s not mean to his staff so much as dismissive of their personhood and feelings, only focussing on the bank and profit. We know early on he has a child and wife he feels affection for, but that’s as far as human warmth goes for him. As Gore-Hepburn’s scheme to steal thousands of pounds unwinds, and Fordyce is forced to become part of the heist, he must confront what he has become, what is really important to him, and reconnect with the world he lives in. It’s an uplifting, very human film about hope and change and our ability for both that is just as needed in these modern times.

The Christmas trappings aren’t window dressing either. The time of year the story is set is intrinsic to the mood and atmosphere of the piece and to Fordyce’s journey. Of course, it’s a fine film that could be shown at any time of year. But what it says about us as people is a classic Christmas message. If you want a beautifully judged thriller, full of quotable dialogue, with one great scene after another, excellent performances, and something to say about what it means to be alive, this is it.